The camel and I have something in common: we’ve both been called ‘refractory’. The camel in a memorable poem by T.S.Eliot titled The Journey of the Magi, and I by my paternal grandmother on more than one occasion. (She knew using ‘big words’ would get my full attention, more so than a whack or a holler.) There the similarity ends.

I could fade into the sea of grey-haired grannies in my city with ease, but a camel sauntering down the street would attract a crowd. They are such clownish-looking mammals with many features to excite a paintbrush or sketch pen. The camel was a favorite subject of one of China’s late, great painters, Wu Zuoren 1908-1997), renowned supposedly for his ‘depictions of natural scenery’. Most of us who study Chinese Brush Painting (CBP) think of him as the ‘camel guy’.

I’ve looked at Wu Zuoren’s work before, admiring his pine and crabs. I saw examples of his camels, but never truly LOOKED at them. That all changed when a FB friend posted a video of Wu rendering a pair of his favored mammals. I was struck by two things: he started with body strokes (not the eyes and head) and he manipulated the ‘halo’ effects of overlapping grey washes to define muscle groups in an amazing manner. He also had a lot of fun defining comical facial expressions with those distinctive eyelashes, nostrils, and lips. Why hadn’t I noticed before?

Now I wish I could ‘share’ a link to that video but unfortunately it was posted to a Chinese website I can’t navigate (See blue screen above). Wu’s method is enlightening to watch, and I was able to see his ‘process’.

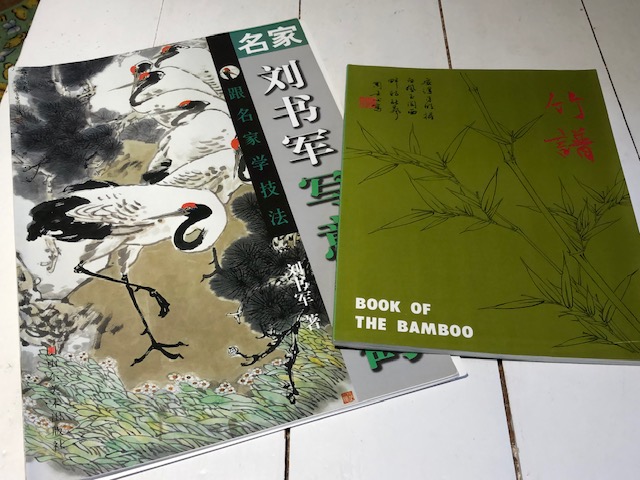

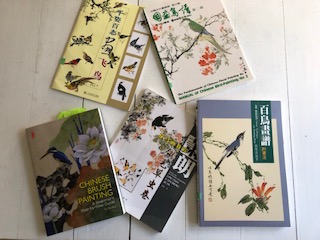

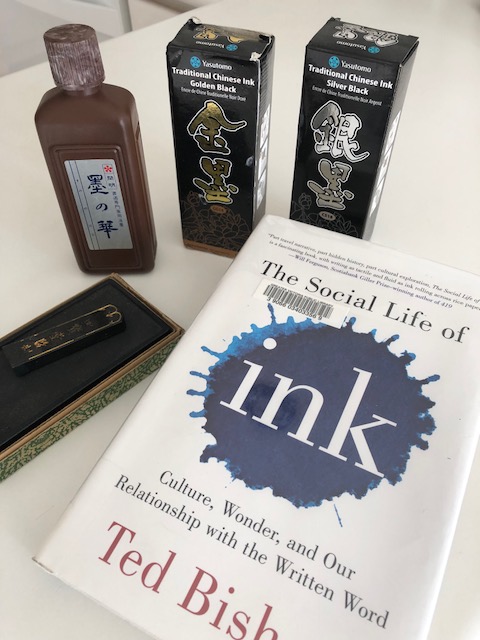

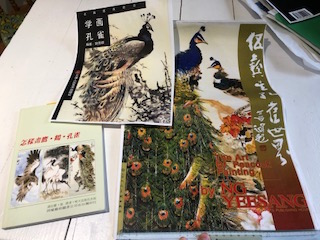

Resources:

Once I was attracted to painting a camel, I had to research what the critter was all about. I knew they were affectionately dubbed “ships of the desert” and were once believed to store water in their humps. (It is fat they stock in reserve in those humps—one for the dromedary and two for the Arabian or Bactrian—and they can go for long periods of time without consuming water, and then they will slurp up gallons at one go.) I found a couple of books on camel painting in the CBP manner, and pulled out all my Wu Zuoren references.

- Selected Paintings of Wu Zuoren and Xiao Shufeng

- Mix Painting Camel (Chinese ed.) by Li Heng Cai

Distinctive features:

The Bactrian camel has numerous features that lend themselves to the nuances of Chinese brush painting. The long, upward-curving neck holds the head at a funny angle, contrary to the smooth neck of a horse, donkey, or even water buffalo. The head itself has those big flaring nostrils (that can be closed to keep out sand) and marvelous eyelashes. The animal also has numerous sets of eyelids to protect the eyes, including one set that wipes sideways like windshield wipers. The head topknot and small rounded ears also contribute to a haughty, disdaining demeanor. Add the fact they spit regurgitated stomach contents when in a bad mood—who wouldn’t be in a Zoo or after long trek over the desert—and you’ve got a most arrogant beast.

The following illustrations are from Li Heng Cai’s book; even without command of the Chinese language I can discern significant anatomical features and their relationship to other body parts.

As for the rest of the body, Wu zeroed in on the hairy clumps atop the humps, the head, the chest, shoulders, knees and toes for great brushwork. He depicts many rear-end views of camels likely because of the ying-yang effects of slim tail contrasting the rounded butts. He also captures the gangly stride (camels walk with the two legs on each side in concert, unlike horses; this result in that distinctive swinging motion some say is the reason for the ‘ship of the desert’ metaphor.) The leg bones are shorter than in horses, and the feet appear flatter (two-toed and heavily padded for efficient walking in sand).

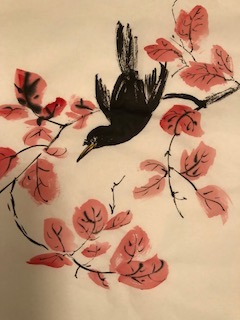

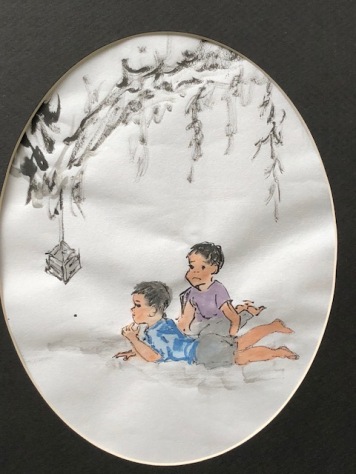

My camel studies:

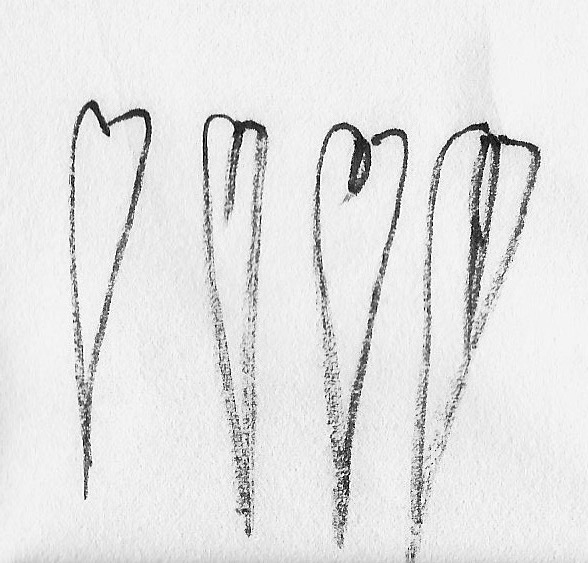

I first had to spend time with my sketchbook, working out the proportions and relationships among all the distinctive camel facial features. The only real life camels I’ve examined were zoo residents who kept their distance and spit if they came close. I had to find photographs as well, as one should never trust another artist’s sketches to be anatomically correct, especially a CBP artist (exaggerating certain features to enhance the spirit of an animal is par for the game.) Here are some sample pages from Li HengCai’s book that offered lots of fodder for my camel sketching:

Then I discovered command of ‘halo-painting’ had slipped my mind. So, playing with overlapping grey washes was in order.

Finally I moved on to trying whole camels. I started with the eyes and head, as the approach was more comfortable for me. I cannot see why Wu starts with the body anymore than I can grasp why the great horse-painter Xu Beihong starts with the body and neck, not the eyes or head. My only surmise is they like to establish the ‘rounded’ belly/trunk first in order to position the animal, kind of like squaring off in a wrestling or boxing match. My first camel paintings:

I want to work on ‘halo painting’ more and using various ink tones for effect. The comical expressions on camel faces intrigue me. And I discovered I have instructions for painting camels using brown colors in a Rebecca Yue book, should I want to go beyond these monochrome studies.