If you would be happy, grow chrysanthemum. (old Chinese proverb)

As a gardener, I’m not fond of the chrysanthemum: the plants are too similar, the flowers all roundish pom-poms, the color range is largely earth tones and strong yellows (I like creams, blues, roses, mauves), they give off an unpleasant fragrance… As an artist then, I’ve had little reason to want to try and capture its spirit on paper.

Because the plant is one of The Four Gentlemen, those all-powerful, all encompassing subjects to thoroughly learn when you take up Chinese Brush Painting (CBP), I’ve had to reconsider the mum. You’ll notice I’ve left it until last among my self-directed, intensive studies of the four fundamental subjects, the ones you learn in order to have a complete foundation for tackling any other subject under the sun and beyond (dragons be not of this earth but are a favorite CBP subject.)

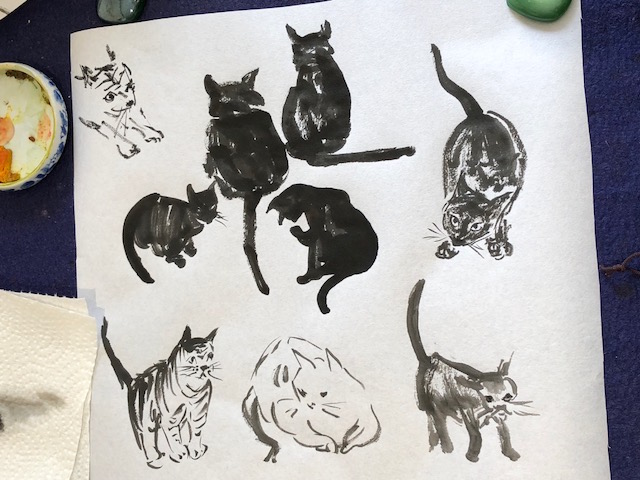

Now that I’ve taken some time to get to know this ‘gentleman’, I feel a little foolish that I didn’t tackle it more thoroughly, much sooner; there is much to learn about painting from this ancient and enigmatic darling of the orient. My studies have expanded over several weeks and have focused on numerous aspects; they are certainly not comprehensive as that could take a lifetime or two!

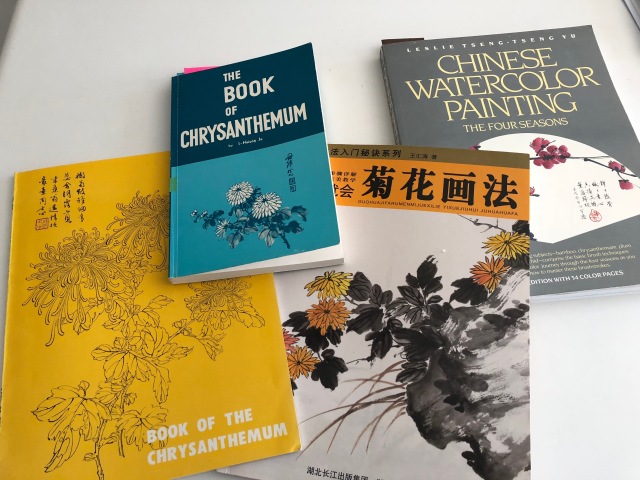

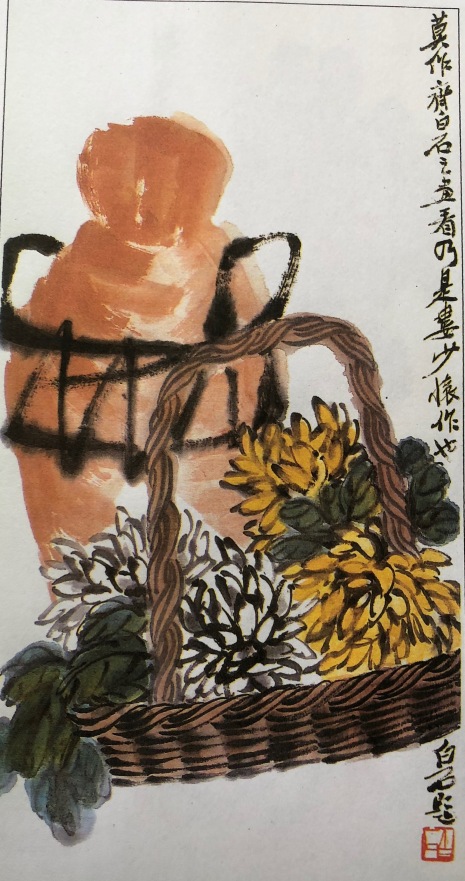

The master painter Qi Baishi identified particularly with the chrysanthemum and painted it often; his mum-painting ‘style’ is very minimalist and quite recognizable. Here are a few examples of his wonderful mum paintings.

This slideshow requires JavaScript.

What is the ‘mum’?

Some online sources report that mums are the biggest sellers worldwide, outstripping roses. I can see the appeal in cheap, colorful, and availability, but I also know many a mother and grandmother who would prefer gifts in corked bottles to those in dirt-filled pots.

I knew that chrysanthemums (family Asteraceae) originated in Asia where they were cultivated as far back as 2500 years. In North America and Europe they’ve had our green-thumb attention for only about 200 years.

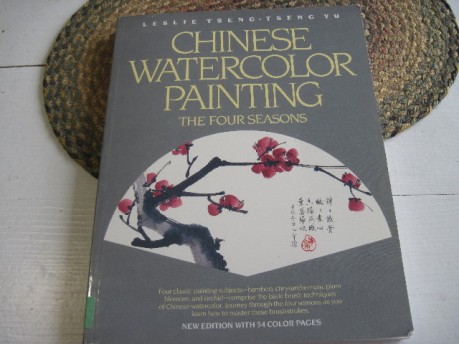

Heaven Full of Stars, Goose-feathers Tube, Carrot-threads, Dragon’s Beard, Jade Saucer Gold Cup. Drunk With Wine Made From Peaches of the Immortals—these are but a few of the exotic-sounding names given to varieties known in China, according to Leslie Tseng-Tseng Yu, author and illustrator of Chinese Watercolor Painting the Four Seasons. Only recently I discovered a chapter in a 1926 book by Francis Ayscough titled The Chinese Idea of a Garden in which she too offers such exotic-sounding names for many different varieties of mums. In the very beginning—some 3000 years ago—there allegedly were only four colors: white, yellow, blue and red.

The National Chrysanthemum Society USA separates the varieties of chrysanthemum into 13 different classes based on floral characteristics: irregular incurve, reflex, regular incurve, decorative, intermediate incurve, pompon, single and semi-double, anemone, spoon, quill, spider, brush or thistle, and unclassified or exotic.

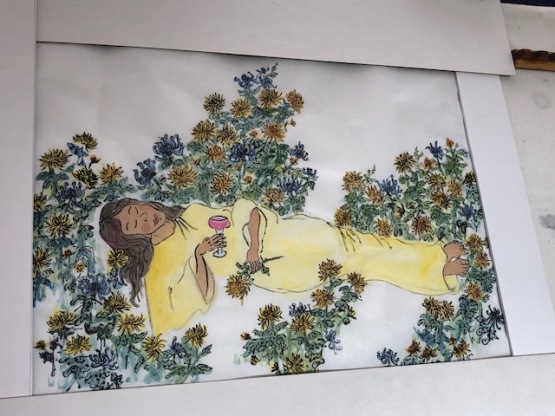

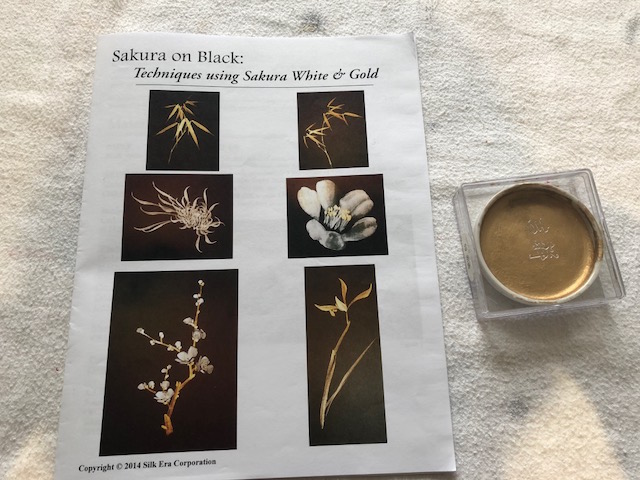

Within these classifications, there are about 40 generally recognized species and thousands of varieties. The Society also offers a detailed history of the ‘mum’. For artists who have been gardeners, mum painting mastery is really more about being selective than thorough. With so many nuances to the flower, one could spend a lifetime exploring its variety. My preferences are for the very simple daisy-like form and the graceful sprawl of the spidery heads. For this reason I started my mum studies examining only TWO painting approaches—1. Outline style flowers with added color, 2. Boneless (moku) flowers in ink and color. For both floral treatments I painted the leaves in boneless style with ink veins.

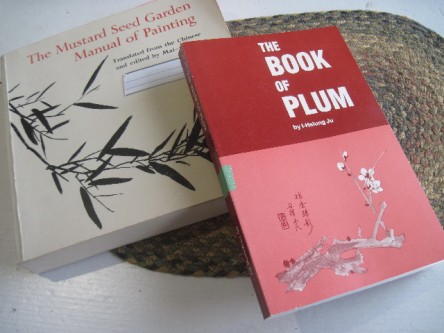

Major resources:

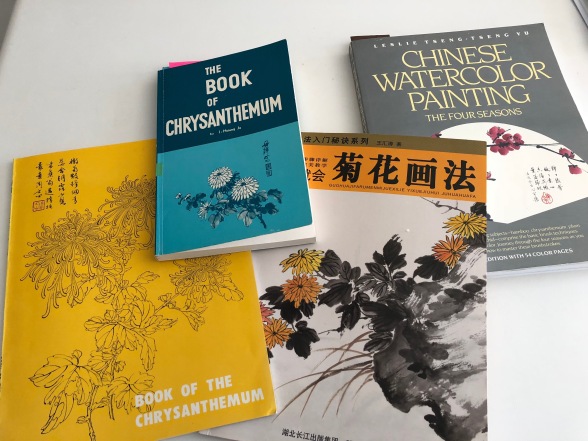

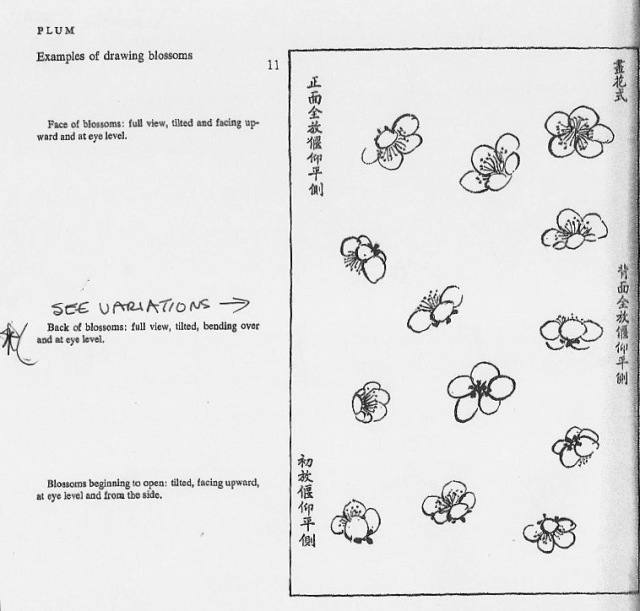

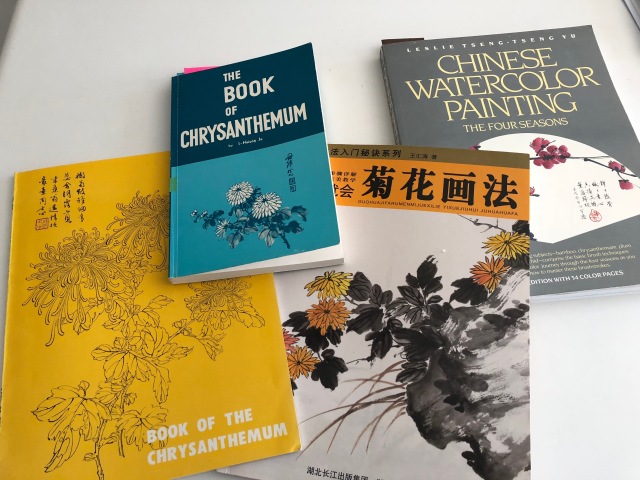

Because of its significance in learning CBP, the mum has garnered a lot of attention; this is reflected in the literature. You’ll find instructions for painting the mum (in at least one style, maybe two) in any general CBP book, as well as in more than a few dedicated to the flower. Most often, it is the last of the four gentlemen (after bamboo, orchid and plum) that one learns during introductory lessons to CBP.

Many CBP artists consider it the ‘gateway flower’ to learning techniques for painting ALL flowers. From my early years in studying this art form I collected numerous books addressing all four gentlemen, and I have also found a few dedicated to painting chrysanthemum. The MOST complete in terms of explaining and illustrating technique is at the top of my list below; the others named are those I rely on the most often.

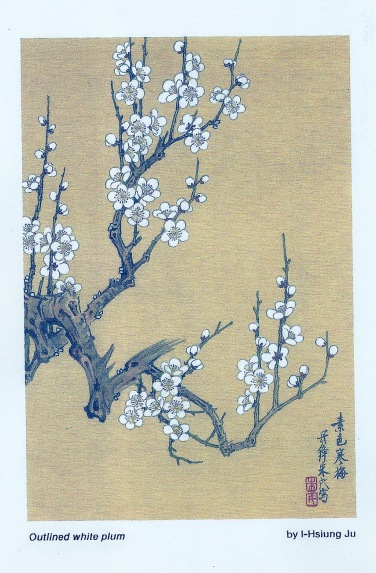

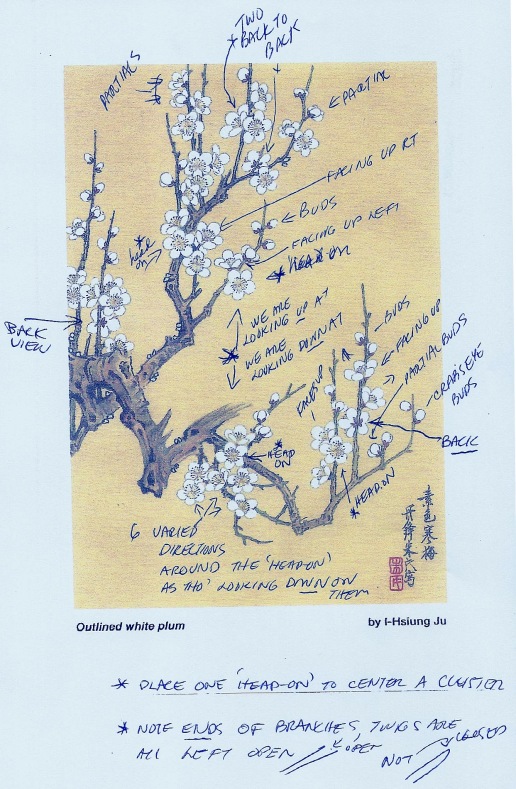

- The Book of The Chrysanthemum by I-Hsiung Ju

- Book of the Chrysanthemum, Vol. 4 of The Fundamentals of Chinese Floral Painting by Johnson Su-sing Chow.

- Learning Drawing Chrysanthemum in a moment (Chinese Edition) by Wang Hui Tao

- The Why and How of Chinese Painting by Diana Kan

- The Way of Chinese Painting, Its Ideas and Techniques with selections from the Seventeenth Century Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting by Mai-mai Sze (handy purse-size paperback)

- Chinese Water Color Painting The Four Seasons by Leslie Tseng-Tseng Yu

- 100 Flowers, Chinese Techniques for Painting Flowers by Yang Oshi.

**. Workshops by Nenagh Molson

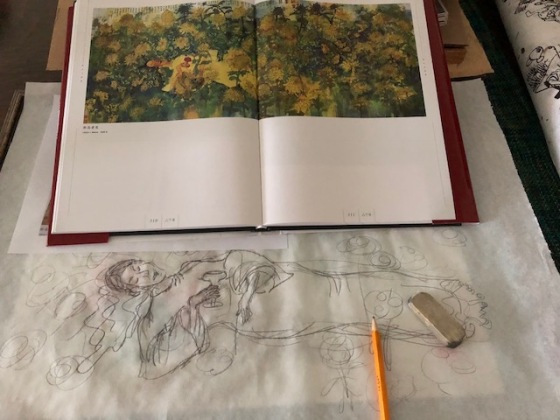

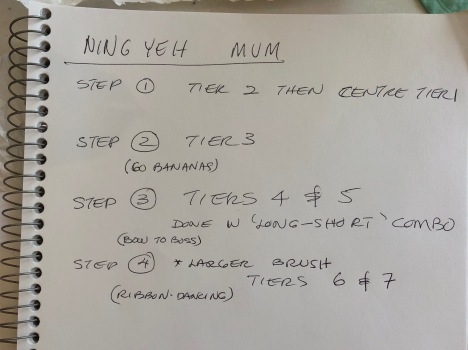

Some of my resources for painting mum; my fav is that little blue book by Prof. I-Hsiung Ju. I also have a handy pocketbook version of the Mustard Seed Garden Manual that is easy to tuck in a bag when traveling or hanging out at a hockey arena.

There are several good videos on Youtube showing mum painting techniques. I recommend five sequential ones each about 3 minutes long starting with this one. (You may have to re-search in order to get 4/5 to come up in sequence.) Note: just the paint application is shown, not the loading of the brush in between bursts of painting!

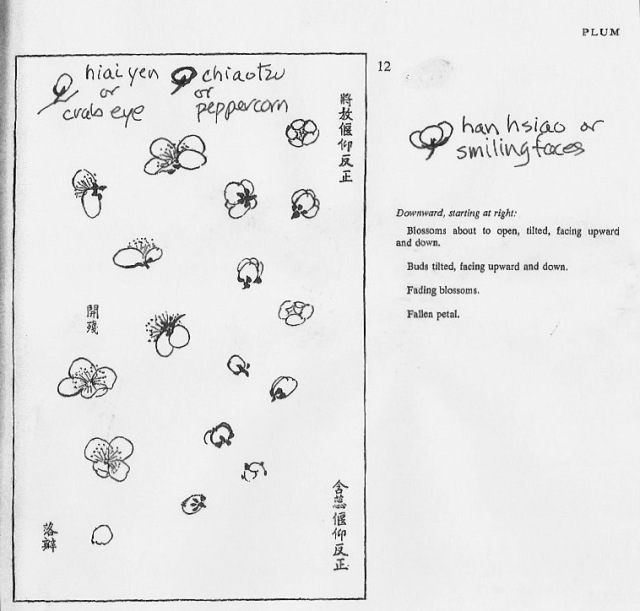

Parts of the mum

As a painter the ‘need to know’ about mums can be boiled down to just a few major parts: 1. buds, 2. flower heads comprised of petals (each one is a complete ‘flower’ in that it has a colorful section surrounding a stamen leading down the throat to a pistil; in maturity the ‘petal’ produces a single seed at its base.) 3. calyx 4. stem and offshoots 5. leaves.

Each part to the chrysanthemum has particular characteristics to be aware of, so that you can capture its true essence. As in all CBP, conventions have emerged and some of the mum’s distinctive qualities do indeed get emphasized and others are downplayed.

Symbolism:

I don’t think I have ever encountered a flower with so many symbolic meanings: cheerfulness in the face of adversity, defiant of frost and triumphant in autumn, intellectual accomplishments, cleansing qualities, joviality and longevity of life.

Buddhists use this flower as offerings on altars because they symbolize powerful Yang energy. This flower attracts good luck in the home. It is good to give old people chrysanthemum flowers because they symbolize strong life. Because of their popularity among gardeners, and the fact so many retirees turn to gardening, the plant has come to represent retirement.

Chrysanthemum is a Chinese word, derived from “Chu hua” meaning “October flower”. It is also the emblem of the Old Chinese Army and, in China, the chrysanthemum has long been considered a very noble plant along with the orchid, bamboo and the plum. It was so well thought of that only the noble were allowed to grow the chrysanthemum in their gardens – lower classes were strictly forbidden from doing so. It quickly became so revered it has a festival unto itself—the Ninth day of the Ninth Moon—as well as many legends.

It is said that Buddhist monks first brought the Chrysanthemum to Japan around 400AD. The Japanese Emperors were so impressed and thought so highly of the little flower that they often sat on thrones of chrysanthemums – there is even a book named the “Chrysanthemum Throne”. To this day, the Japanese believe that the chrysanthemum is a symbol of the sun, and that the way in which the flower opens its petals denotes perfection. Japan also holds a “chrysanthemum festival” known as the Festival of Happiness.

As with many flowers, the Greek language comes into play with the naming of the Chrysanthemum. The name is believed to derive from “chrysos” meaning gold, and “anthos” meaning flower.

In some European countries, the chrysanthemum symbolizes bereavement – most notably in Italy, France, Belgium and Austria. Chrysanthemums are only ever sent in these countries at a time of sadness, death specifically. In the UK however, the chrysanthemum holds a much more positive sentiment, used widely in all lines of floristry. Florists, customers and recipients alike often cannot fail to love the vibrant colors and wild shapes of this most versatile flower.

Composition in paintings:

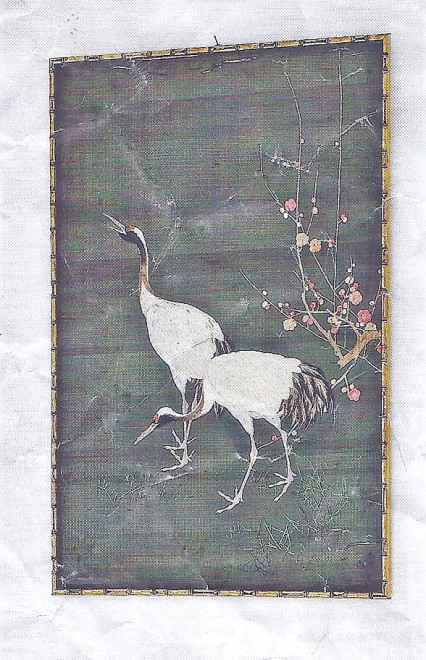

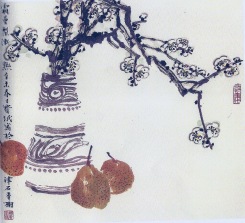

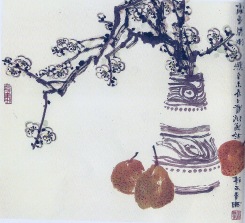

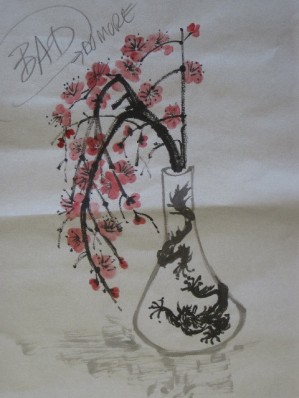

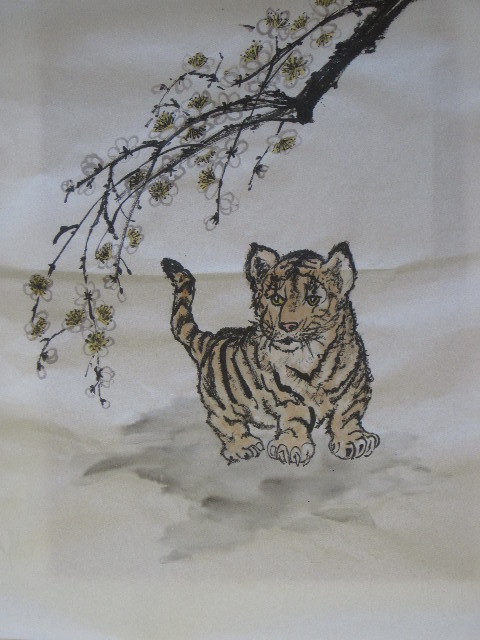

Traditional portrayals of mums in CBP generally fall into two categories: 1. a few select stems on the paper alone or in a vase/basket, or 2. the plant ‘in situ’ as it once was in ancient China, growing beside a rock or next to a bamboo fence.

Lou Shibai’s painting of several chrysanthemum heads in a basket is a classic way to show the flower. I’m impressed by the even basketry weaving.

Painting the Mum in Outline style with added color:

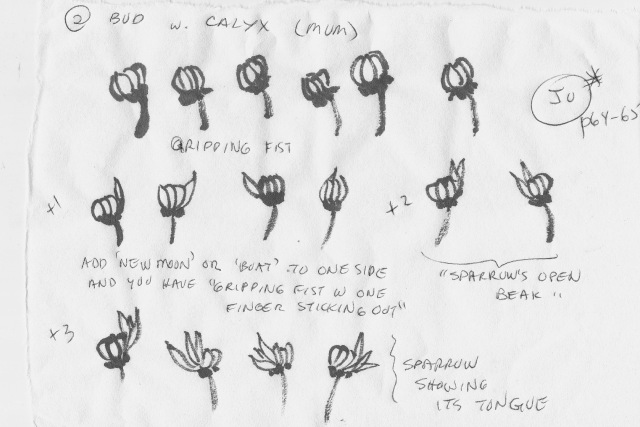

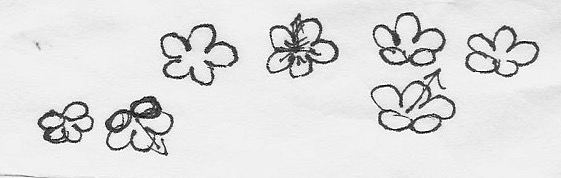

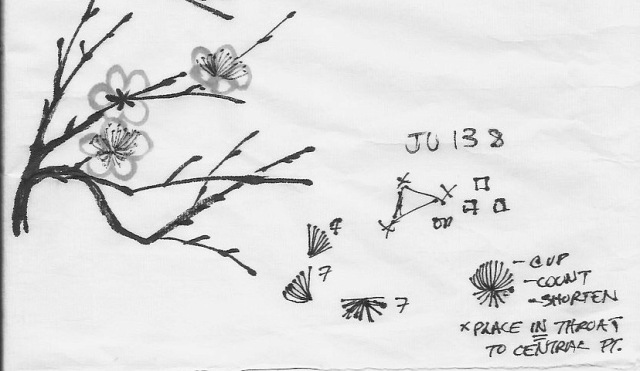

My studies started with attention to floral heads, but once I acquired Professor Ju’s marvelous books on painting the four gentlemen, I realized there was much to learn about the basic petal stroke (kou-le) before attempting to portray full flowers!

Ju offers many insights into the etymology of the term ‘kou’le’ and sums up thusly: “kou” is a line made by a tip stroke with a hesitation at the beginning, a ‘tsang-feng’, then followed by a straight stroke, a ‘chung-feng’, and ended with a reverse movement, a ‘huei-feng’, so that the pointed ending of the whole stroke is returning like a hook. “Le” is a line with the same quality as ‘kou’, but placed horizontally, either in convexity or concavity.

He explains that all chrysanthemums painted by the ‘kou-le’ method will therefore have every petal closed, surrounded, or even limited by either kou strokes or le strokes.

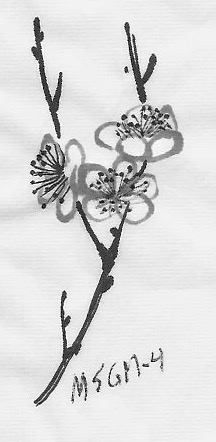

Study sheet 1:

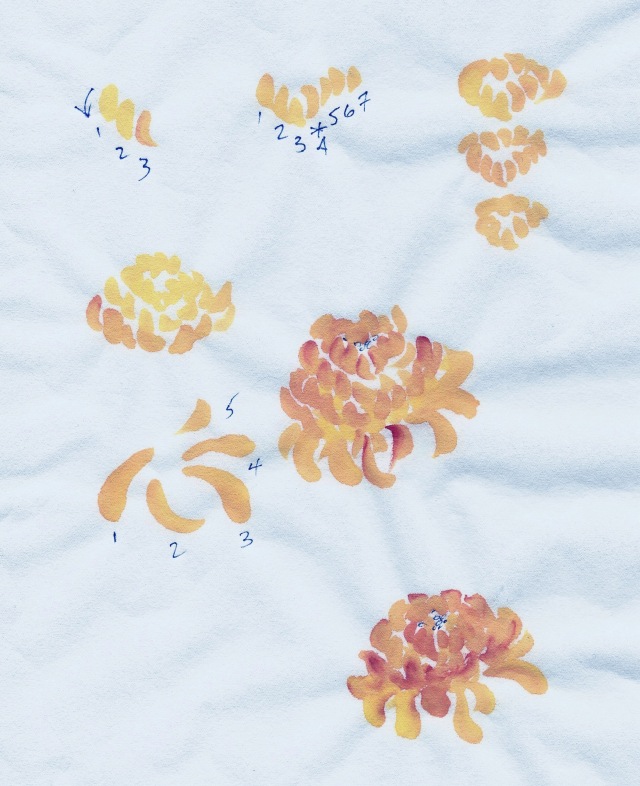

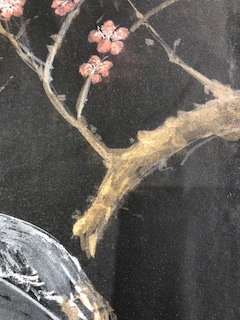

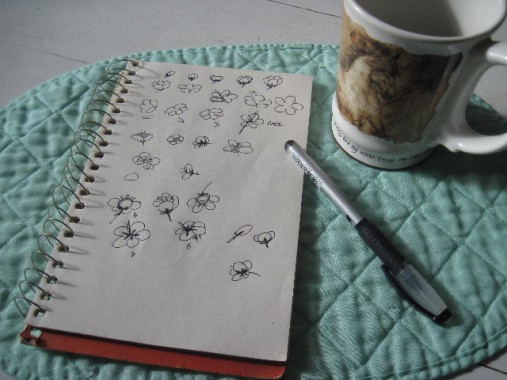

I started with trying the ‘kou’ strokes as used by Yang O-shi to portray a simple flower in THREE steps. She painted her centre stamen dots first and then pulled the petals in toward the centre.

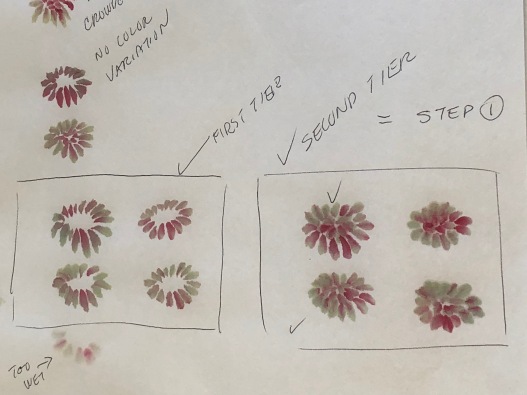

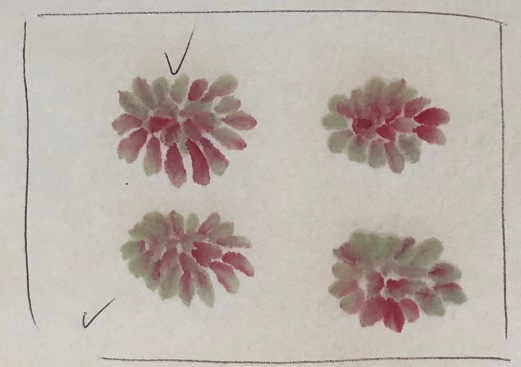

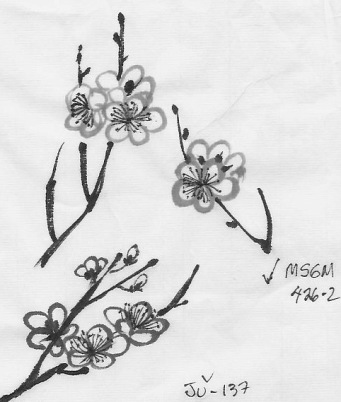

In a recent workshop Nenagh Molson explained that the ideal centre dots are added once you have outlined the petals around a centre space, they should all be dark and round and NOT touching one another. Her method involves FOUR steps: outline petals lightly, add dark centre dots, apply variegated color using a brush loaded with water and tipped in color by touch-pressing each petal, then when dry go over the petal outline in dark ink.

Prof. Ju (and others on my list of resources) explains how to foreshorten petals and curve them as you position them in a spiral in order to convey depth (and roundness) to a flower. He uses umbrella shapes to help illustrate the visual concept. Most of them also specify an order to the placement of the petals so that you evenly distribute the petals. Once you’ve mastered a simple flower, they walk you up to layering petals in composite heads, and varying petal length, curl, width, etc.

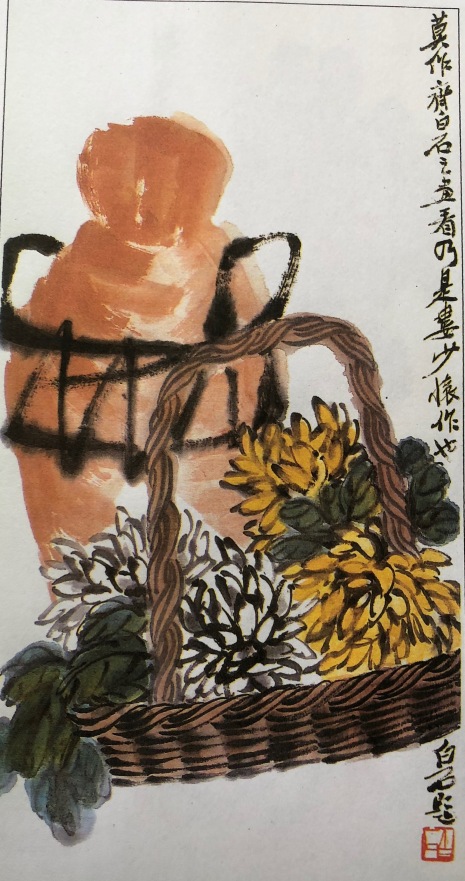

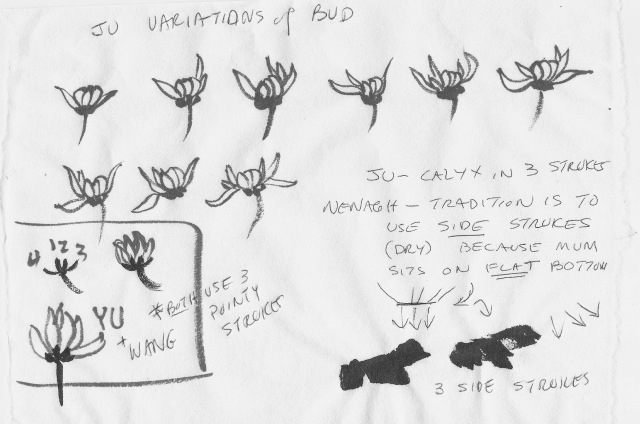

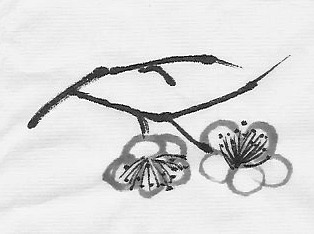

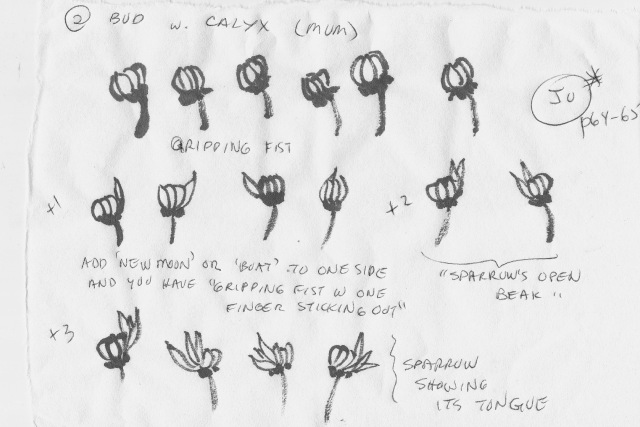

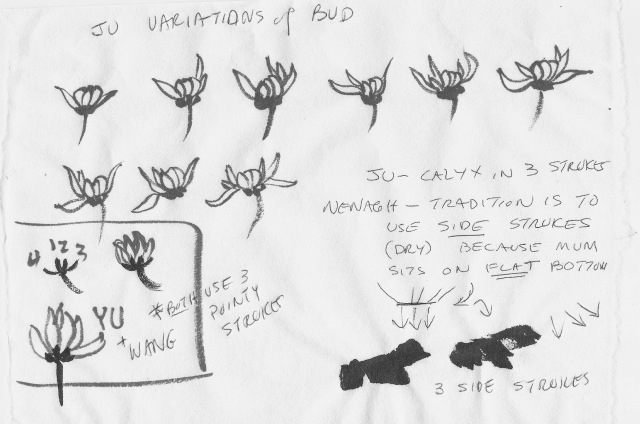

Study Sheet 2 and 3 (a bud and the calyx)

Prof. Ju gives us lots of ideas for portraying a bud. His method for the calyx yields a crisp looking platform for the bud to sit on. Nenagh explained the traditional manner she learned for portraying the caylx; it requires a brush loaded with dark ink used in side strokes.

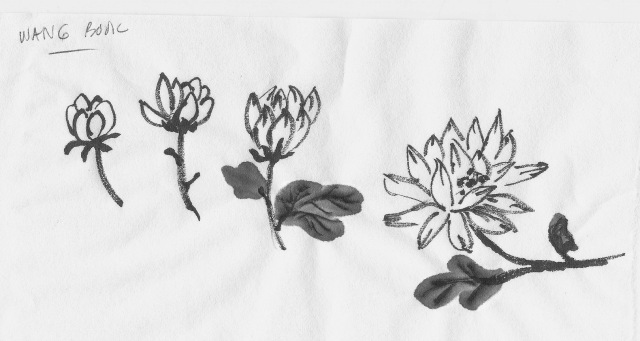

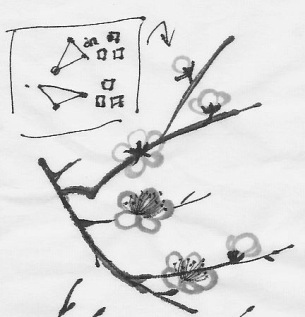

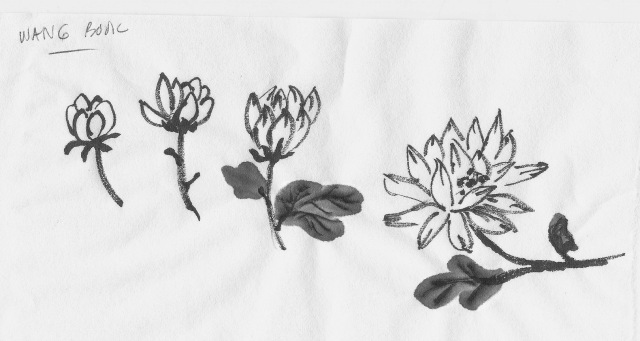

Study Sheet 4 (based on the Wang book method)

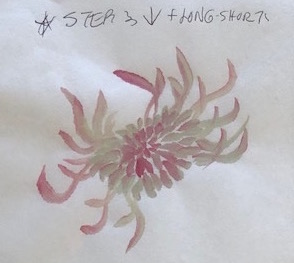

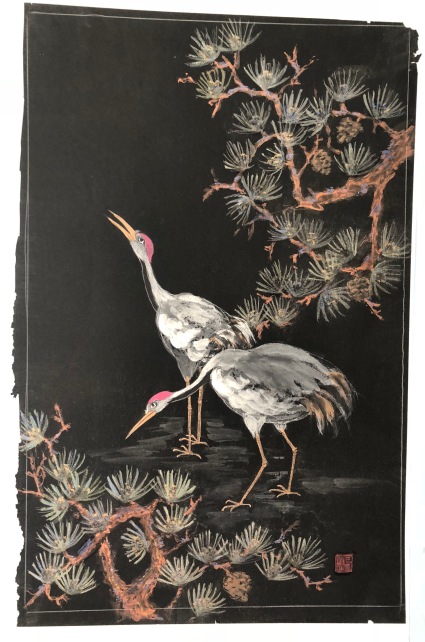

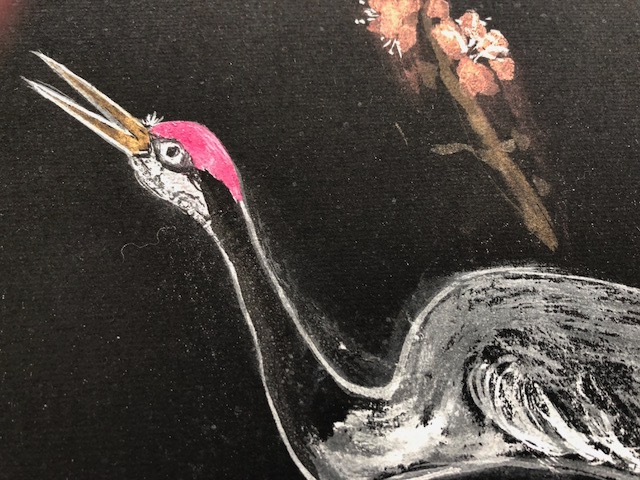

More complex heads are a logical next step for my studies, and I sooooo want to get a better handle on Nenagh’s coloring technique. Here’s some inspiration from her last workshop:

More studies to come, then leaves.