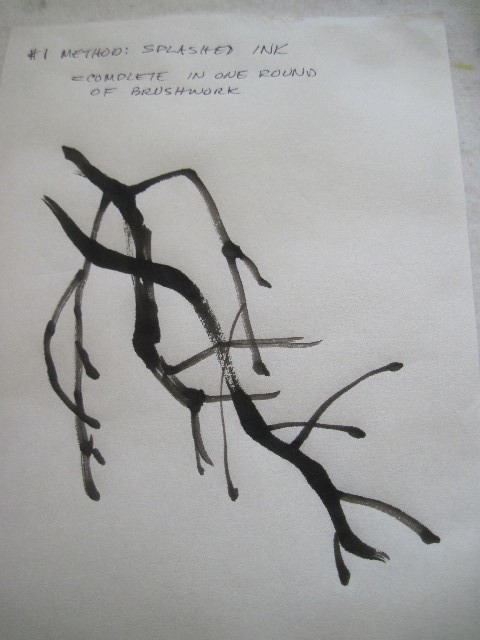

You have to understand some principles of abstract art before you can ‘get into’ what Picasso was doing with his ‘cubist’ approach, breaking up subjects or objects into pieces and re-arranging them to suit his own mind. You may need a primer on the nature of pointillism to grasp what Seurat was aiming for with his colored dotting technique. Likewise, when studying some of the CBP compositions from ages past, you do need to have some understanding of the principles of composition, the nature of brushwork, tonalities of ink, modeling methods for texture, and so on.

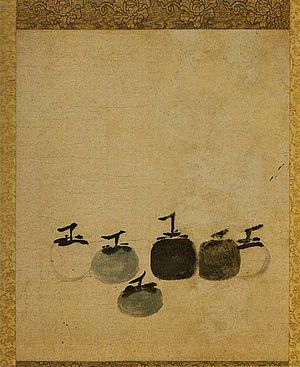

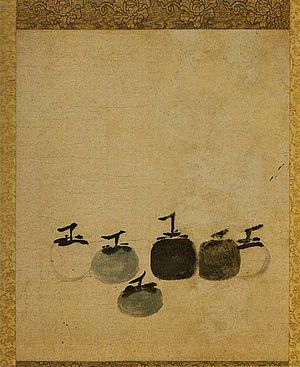

The need for context is never more obvious than when examining one that is highly touted. When I first tripped over the 13th century Chinese painting titled The Six Persimmons, attributed to the monk, Muqi Fachang, or Mu Ch’i Fa-Ch’ang, my curiosity was hugely aroused. Just what was all the hoopla about? And why was it housed in Japan? It has been billed as the ‘ultimate in painterly simplicity’.

.

For more about the painting see this entry.

Berkeley’s Professor Emeritus James Cahill devoted a full half-hour in his lecture series (lecture 12 part 2) on landscape painting to exploring the mysteries of The Six Persimmons. Here is just that lecture.

And here are his lecture notes which I found after I’d laboriously made my own!

Introducing the Zen (or Cha-an) Painting:

Some grasp of what constitutes a Zen (Chan in Chinese) painting and history of their development helps in the understanding of Cahill’s lecture, but he also integrates such background into his talk. Basically it’s a genre of CBP developed by a particular sect of monks and shared with other literati, in which the artist creates a simplistic composition–usually of a very common subject such as a vegetable–employing some painting techniques that instills in the viewer a sudden epiphany or moment of illumination. The arrangement or treatment of certain elements within the composition command attention in a powerful way. The small painting featuring six little persimmons was shared among Zen Buddhists monks, including those in Japan where it now resides. It is much admired by art critics and artists in both countries.

The closest thing we have to a Zen painting in the western world is perhaps the still life.

Back to the Six Persimmons:

To illustrate one of the principles at work in the Six Persimmons, Cahill shows us a landscape grove composition featuring several trees painted in similar yet different shapes (i.e repeat patterns), all with varied (contrasting) tonal values. He draws attention to the location of the darkest one—just slightly off centre—and proffers that the three elements (darkest tone, central placement amid similar shapes) cause our eye to see the grove as we would in nature; the one darkest tree gets our attention and hence is the focal point.

Cahill goes on to show paintings done in China, in the manner of Muqi, that were kept in China. None of them has the liveliness, the mysterious immediacy that his simplistic Six Persimmons composition does.

In Cahill’s lecture he provides several visuals to illuminate his insights into why this little painting warrants attention. In one comparative slide he shows Muqi’s Six Persimmons beside a handscroll painting of eleven persimmons completed by some unknown copyist; the fruits are all too similar in tone, shape and brushwork to warrant much attention.

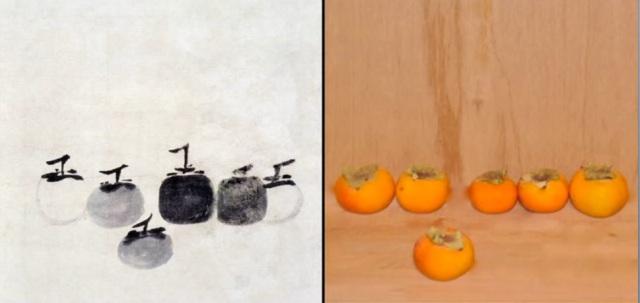

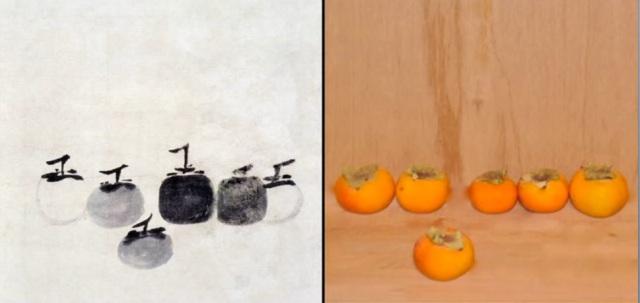

Two other comparative slides from Cahill’s lecture I’ve captured and present below.

The first places the subject painting next to a photograph of six real fruits; a friend of Cahill’s took the photo in jest, but the professor of art used it to show just how complex the painting really is. The photo does line up six fruits in a very similar manner to the compositional layout, however there is little to distinguish the individual items: stems are too similar, color tones are very similar, shapes are similar, and so on. Muqi’s arrangement and treatment went a long way to convey multiple contrasting messages.

Later, Cahill shows two small paintings of a similar subject—chestnuts on a branch—with one painted in traditional manner and the one on the right presumably done by Muqi (Cahill provides several strong arguments as evidence).

The differences in tones used for the leaves, the mixed and rough textured brushwork to convey leaf surfaces, the vitality and multi levels of interest in the Muqi composition all contribute to the commanding presence of the composition. Such was the intent for a true Zen painting; a simple subject, painted with great care, aiming to command a viewer to GAZE at it.

In essence, The Six Persimmons comprises exactly what the title says: six garden variety persimmons are painted in shades of ink—greys through darker blacks—across the page. They appear to be placed relative to one another with some plan. Each one has some individuality, and each has some ‘roundness’ or depth to its presence. They are not flat on the page, they are not just tossed on a table out of a basket, and the tonal qualities of the ink goes a long way to portraying degrees of firmness or ripeness in the fruit.

If like me, you have read and re-read passages in the Mustard Seed Garden tome or other books on the theoretical aspects to CBP, you’ve wrestled with things like the following:

“Neither complexity in itself nor simplicity is enough.”

“Neither dexterity nor conscientiousness is enough.”

“To be without method is deplorable, but to depend entirely on method is worse.”

And finally:

“You must first learn to observe the rules faithfully; afterwards, modify them according to your intelligence and capacity. The end of all method is to have no method.”

My books on theories behind Chinese Brush Painting (CBP) are rife with such loaded statements that can leave you pondering for hours. I often consider there may be even more I am missing because of translation! But there is no doubt in my mind that Muqi’s little painting has a lot happening in it, and I do want to know what those things are.

Resources on how to paint persimmon:

My main resource on techniques for painting the persimmon is the (Book 2) Fruits volume of Johnson Su Sing-Chow’s four-volume set. It is shown here next to my pocket-book size version of the Mustard Seed Garden, which is so handy to take along to thumb through when gifted with lumps of wait-times in odd places.

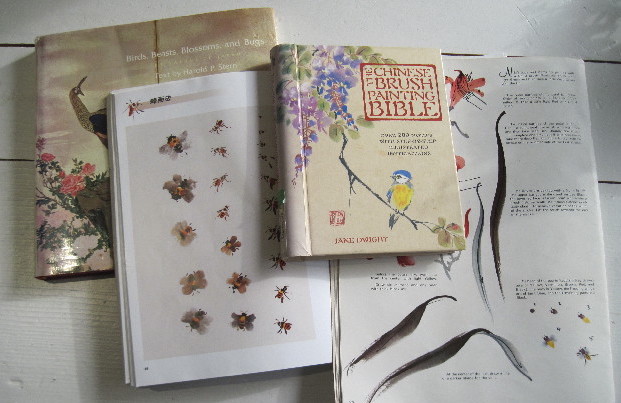

He illustrates painting the heart-shaped persimmon (most likely an ‘hachiya’) that is grown in North America and the copper-basin, a large sweet fruit that is rather flat in shape. Jane Dwight, in the Chinese Brush Painting Bible, that handy little spiral bound compendium, shows a similar approach with side-stroke fruit (her choice is the stacked Tam-tams or maybe Tamopans) and double side-stroke leaves. Both finish off their broad leaves with a little tip to the leaf, which neither have described in the text; you have to catch that tip from the visuals.

What is the persimmon?

From Su-sing Chow I garnered that there are two main kinds of persimmons, those that have soft pulp and those that have hard pulp. Soft-pulp varieties, also called sweet persimmons, are mainly red and ripen on the tree. The hard varieties (bitter persimmons) are mostly paler colors and can be quite unpalatable due to their astringent tannins. They need to be fully ripe before their chemistry alters the bitterness and the pulp becomes both palatable and digestible.

Art group member Jany Li brought a frozen persimmon (large and flat-shaped so probably was a ‘copper basin’ variety) to our group coffee break one morning, telling us on her recent trip to China she’d discovered this way of serving persimmon so as to enhance the flavor. The jury is still out on that one, as we had mixed opinions.

While hunting through my big C.A.S. Williams book on symbolism in Chinese culture for his ideas on the persimmon, I noticed he said the most widely propagated varieties are often picked after exposure to frost, which sweetens the pulp and boosts the nutrition level. That sounds like what we Canadian gardeners do with broccoli and other such vegetables, and likely what Jani’s home freezer had accomplished.

Persimmons originate in China and are deemed a fruit of good fortune and an emblem of joy. They are cultivated in every part of China except the extreme cold regions. Williams mentioned one called ‘large millstone’ that can reach 18 oz. (500 g.) or more by weight. Some varieties are native to North America; all are in the family Diospyros and go by common names such as ‘date plum’; the variety D. kaki is the most widely grown.

The persimmon tree is deciduous with broad thick leaves, and pale yellow flowers. Fruit come in many shapes—ovals, spheres (Hachiya is the most widely cultivated one), square-ish lumps (Sheng ), and one distinctive variety (Tam o pan or Tamtams) even looks like two fruits stacked, or one that wears a cap in the manner of North American acorns.

Here’s a link to a California blogger who shows us a range of varieties and do note the green leaves next to ripened fruit in some photos; other photos show trees with fruit but no leaves, as they have fallen. (Under ‘painting technique’ later on I will pass on advice to avoid green!).

Fruit sizes vary, as do the reddish colors. Of course there are many ripening into the orange tones widely called ‘persimmon’. See this link on the color name.

This sheet showing numerous varieties of Persimmon is from an agricultural information sheet.

These are the Tam-o-pan variety that appear to be two stacked fruits, or one with a waist; the photo is from San Diego Magazine.

The ‘Seven Virtue Persimmon’:

Ancient Chinese lore has it that persimmons are valuable on seven fronts: they live long (about 80 years), provide good shade, offer good bird nesting, do not harbor pests/parasites, they can be used for fall decorations, are good to eat, and the fallen leaves are broad enough to write on. The painter Zhang Daquin called it the ‘seven virtue tree’.

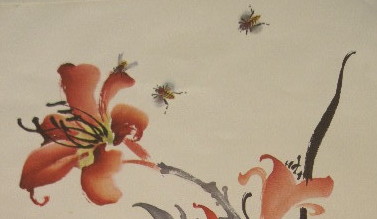

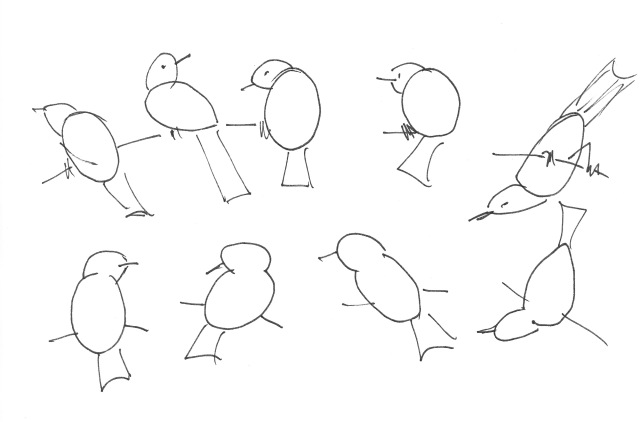

Persimmons are commonly painted with birds; or with an herb called lingzhee to convey the greeting ‘may all your wishes come true’. I stumbled upon persimmons as a subject of interest when I found some odd little birds perched among them. While studying sparrow I became intrigued by painting birds head-on; getting the eyes either side of a flat stroke for the head offered a challenge. Two sparrows in this pose in a persimmon tree showed up in a Google search more than once. They got my attention and then The Six Persimmons commanded my attention.

Steps in Painting Persimmon:

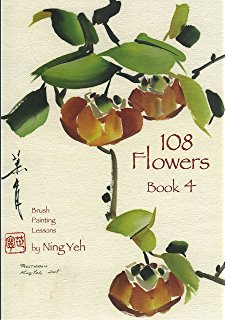

Whether rendering persimmon in ink or color you’ll need some knowledge of the distinctions of their parts: stems, leaves, peduncle, calyx and fruit. Su-Sing Chow paints both heart-shaped (hachiya) and stacked (Tam-tams) using ink tones for the leaves and color for the fruit; he says avoid green for the leaves suggesting they have turned to fall colors when the fruit would be ripe, so fresh green would not naturally appear next to red fruit. Dwight also shows the pairing (ink leaves and colored fruit) and the few online comps I have found involve ink-toned, greenish or brownish washes for the leaves. Ning Yeh’s recently published Book Four (108 Flowers) in his series of Chinese brush painting lessons, features persimmon on the cover; his treatment is distinctive and it does use green for the leaves. (The book is on my wish list!)

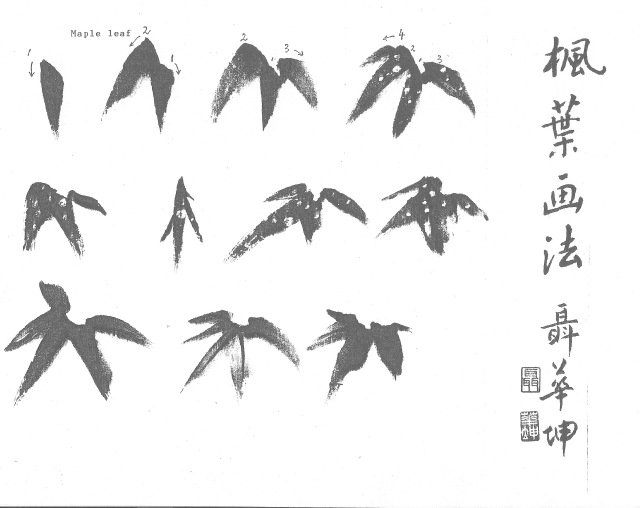

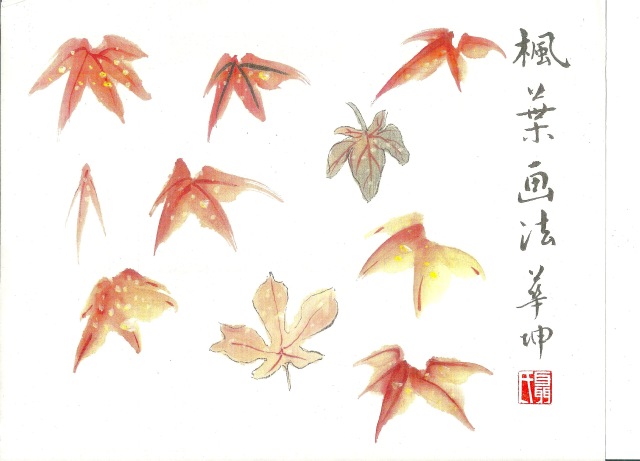

Painting the leaves:

Paint leaves first, aim for large size relative to fruit, avoid green as the leaves have fall colors or have dropped by the time fruit ripens.

Plan the comp with leaves and stems intended to surround a few feature fruit; you may be swiping in the fruit so they are behind a stem or partially screened by a leaf.

Bigger leaves require two strokes. Use water and ink, with some brown. Differentiate between light and shade (lighter ones behind fruit, on top of the tree where sun hits them; darker for undersides or out of the sunshine.) You may have to come back and tuck in leaves or parts of leaves behind fruit once they are done/dry.

Add veins to leaves when damp; though parallel they must not be uniform.

My first study sheet of persimmon leaves; the brownish-ink I thought I had applied in tones but the leaves dried to similar values.

Painting branches/stems:

“Suspend the wrist and use a centre brush stroke; apply inner strength, move the brush slowly, sustain and disperse the strength of the brush stroke to the very tip of each stem.” says Su-Sing Chow. Strive for crisp and fluent brush work.

Choose spaces for each fruit, close to a branch with room for a short stem/peduncle.

Painting the calyx:

The persimmon has four sepals/sections to the bud that, when opened, lie splayed atop the fruit. They are best outlined in ink with a detail brush, colored partly with umber, and finished with light mineral green.

Dwight left hers outlined only.

Painting the peduncle:

This short little stem that supports the fruit on a branch needs to be crisply done in dark ink. Be sure to tuck the stroke end back on itself and not just stop smoothly.

Painting the fruit:

Depending on variety portrayed—heart-shaped ‘hachiya’, larger and flatter ‘copper basins’ or the stacked ‘Tam-tams’ –the brushwork used involves side-strokes of color. You can play with loading a brush with orange dipped in reds. For the heart-shape you employ two paired strokes, for the stacked you place c-shapes one above the other.

Work from left to right, from top to bottom of fruit; then place the right to left stroke if doing heart-shapes. Patch up any ares with the brush tip to fill in the shape.

Leaving a bit of white showing between the strokes is desirable as it suggests light gleam on fruit; it also retains some of the curving look (3-D) to the fruit.

Use a larger soft brush

Practice to develop a ‘feel’ for the wetness, the color blending, the speed of the strokes, etc.

I tried both heart-shaped fruit and stacked ones. The bit of mineral green on the sepals has a nice effect.

Planning a composition:

Think out an arrangement ahead of time, such that the fruit can be shown with varied ‘faces’. Details of the four sepals go a long way to help convey the ‘turn’ of your fruit. Having leaves on all sides of fruit helps create the desired 3-D effect. Various ink tones in the leaves are desirable. I set up my table and tried to replicate one of Johnson Su-Sing Chow’s exercises:

And then for fun took a stab at the composition found online showing two head-on cartoon-like sparrows:

Emulating Muqi’s Six Persimmons?

I have yet to try painting just the fruit, in just the ink….it’s too much fun playing with orange and red brush loads and the side-stroke shaping of fruit. I’d think mastery of fruit shapes, calyx directions, and crisp little peduncles are all necessary first. Striving for ink tonality and clever placement of fruits in different shapes and configurations will take time. One has to be grateful to the Japanese Zen-Buddhist monks who carefully preserved the Chinese monk’s precious painting. In one of those online sources documenting the painting’s provenance, the story is told of a monk who saved it from a burning building by cutting his stomach open and tucking it inside his abdomen. Apparently the evidence is in a red blood smear on the paper near a corner or back of the paper. Ah, those art-collectors who create myth to enhance value…could it possibly be true?