Growing up in the 1940s and 50s in the Robson Valley we lived through a lot of transitions: from coal oil lamps to electric lights, from wood stove to central heating, from horse and buggy to cars and trucks. In those heady times of modernization we sometimes had to fall back on the old ways whenever the new ones didn’t quite work as they were expected.

This was never more obvious than during the winter when snowstorms plugged up roads and vehicles couldn’t get through until the highway crew (my Dad among them!) cleared the way. There were occasions, such as the annual school Christmas concert at our community hall, which one simply had to attend; yet we often faced snowed-in roads impassable by car. That’s when Dad would simply go out to the barn, hitch up the team, and get us to the concert on time! It wasn’t unusual to arrive to a parking lot filled with some vehicles as well as several horse and buggy combinations.

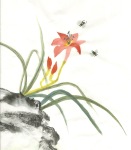

Horse drawn sleigh rides offered as tourist attractions always get my attention. Sugaring-off in Ontario holds lots of appeal for this gramma and her camera.

I’ve blogged about painting horse before, relying on many early memories of horse anatomy and behaviors. The image of two horse rear-ends trotting along in front of our wagon as we headed to the post office, train station, school or neighboring farms is lodged deeply in my brain, both left and right sides.

I can hear the clip-clop of their hooves on the hard-packed country roads in summer, the snorting of horsey breath, the jingling of harness, and even sounds of birds chirping and twittering along the wayside. I can smell the earthy animal scents of sweat, dung, saddle soap and plain old horsehide.

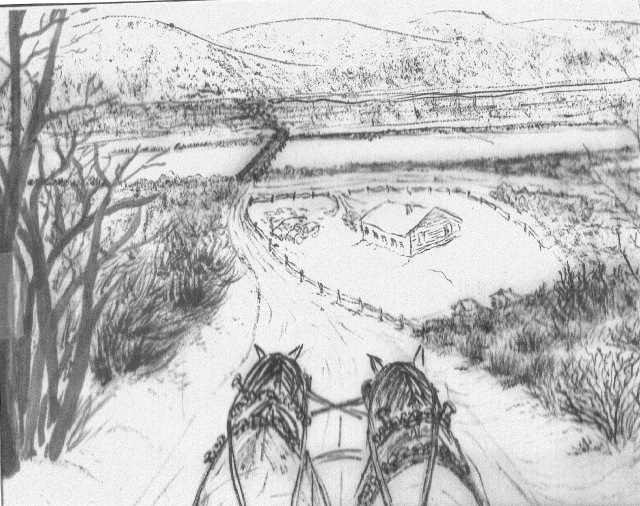

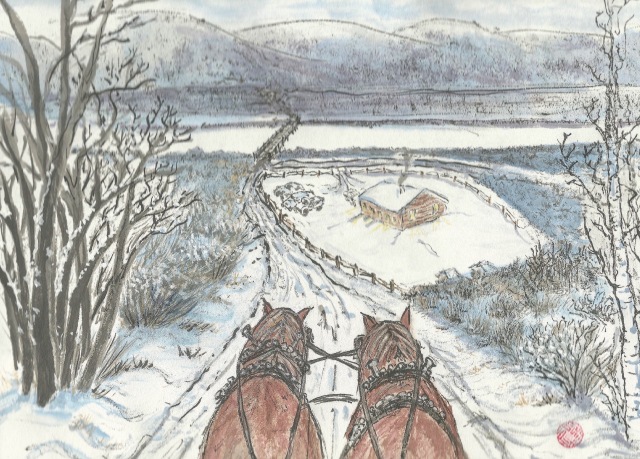

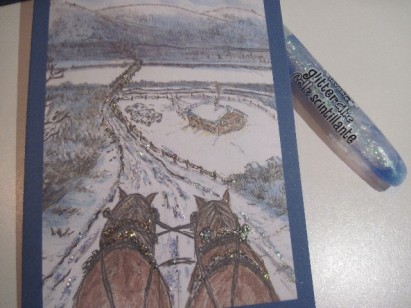

So it is that when I tripped over a painting of a country vista as seen from the driver’s seat of a buggy—yes, staring into the rear-ends of two horses—and ahead to a farm yard nestled in a valley, I was inspired to try and replicate a similar childhood memory. (You can find such images via a Google search using tags such as “snowy sleigh ride images”. Few seem to be tagged ‘rear view horses’.)

My painting plan

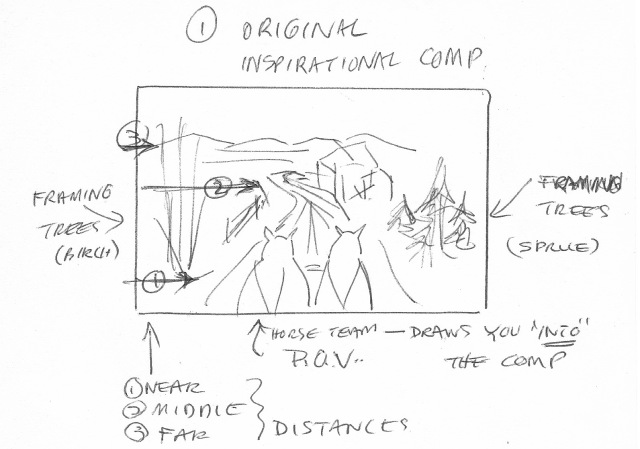

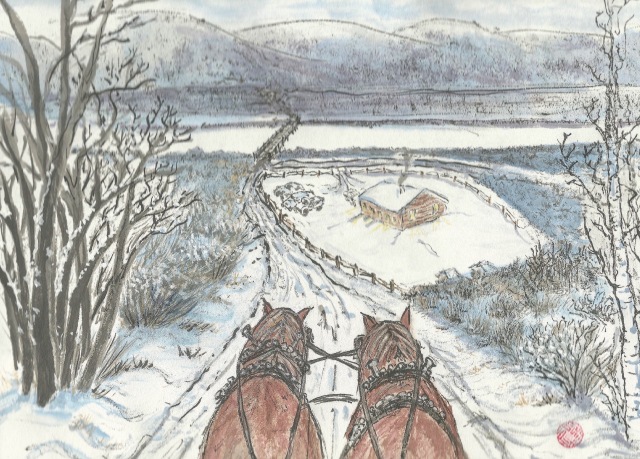

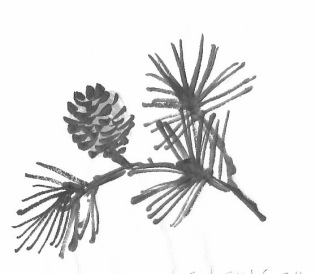

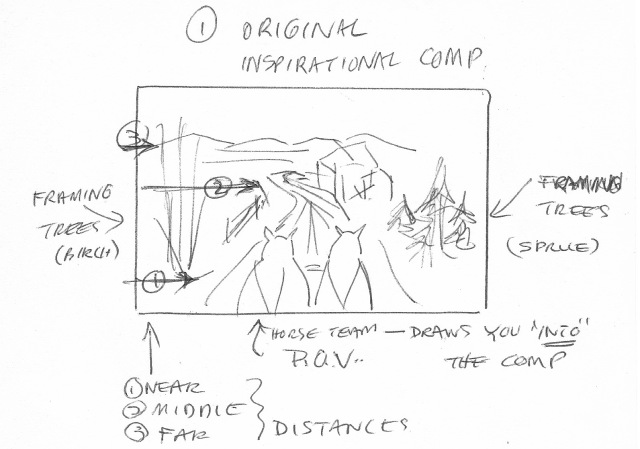

The inspirational composition at first seemed simple enough. The horse rear-ends were front and centre, dominating the scene. To either side were some tree clumps (birches on the left and evergreens on the right) framing the scene. The horses were headed away from the viewer, drawing you into the picture. The visual had depth to it.

And that’s where things started to get a bit complicated. The whole scene was in winter, complete with snowy trees, roadsides, roadway, snow-covered rooftops, and distant mountains. I had instantly determined I could paint the horse; I could depict the trees, the buildings, the middle and far distant elements. There was the small matter of figuring out how to “save” the white of the paper to keep the snow-covered bits looking white, and learning how and where to trail in blue-y lines to define the snow.

There were also two huge challenges posed by the perspective and the desire for some aspect of realism. Yes, I had instantly recognized that the horses in the painting could be my horses, the mid-distant buildings (their destination?) could be my old community hall, and the distant mountains were easily my old valley guards. I was back in time, heading to the Christmas concert with horse harnesses jingling, nose tingling from cold, and my young heart filled with excitement and anticipation.

Inspired and driven by such strong emotional connections some artists can create amazing compositions. Could I be one of them?

The clash between what is/was real and what works for a painting can literally ruin your intentions. The inspirational scene, although having at least three ‘distances’ (front, mid range and far), comprised essentially three, layered, horizontal planes. And this is often the way landscapes are presented in traditional CBP compositions, albeit they are envisioned with certain other principles in mind.

The clash between what is/was real and what works for a painting can literally ruin your intentions. The inspirational scene, although having at least three ‘distances’ (front, mid range and far), comprised essentially three, layered, horizontal planes. And this is often the way landscapes are presented in traditional CBP compositions, albeit they are envisioned with certain other principles in mind.

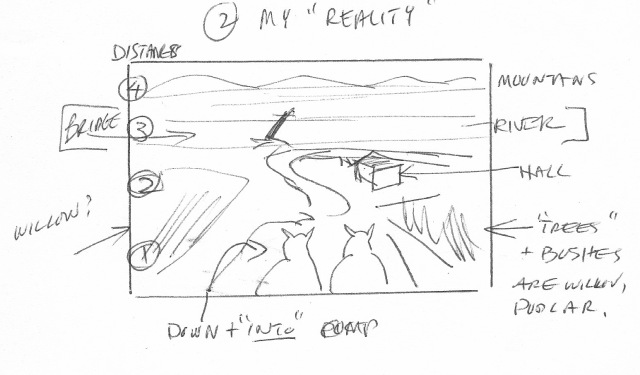

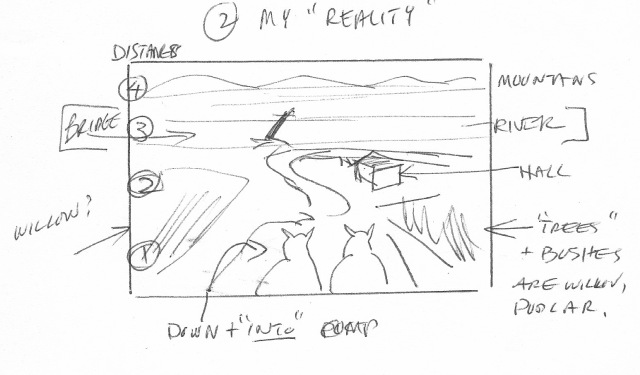

They are fairly easy to sketch. For my remembered scene I wanted to add the sense of descending a hill into the destination community hall, as well as rounding a corner. That’s the way it was: you went down Blackwood Hill (named for the nearby farming family) just before you rounded a corner…and then surprise, you came upon the hall. Of course my childhood nostalgia may be mixing up some of these sensations and perspectives, but that’s my memory and I’ve got the artistic license here!

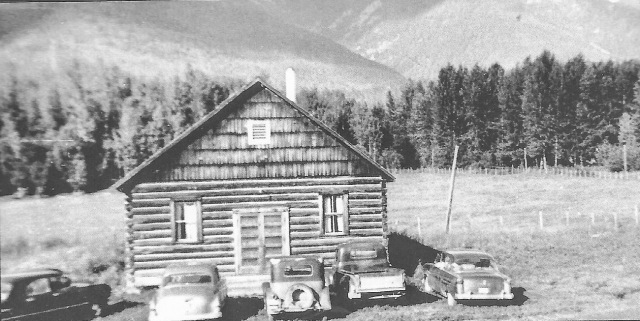

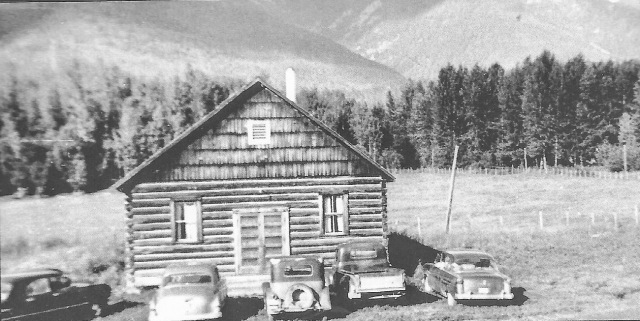

Here’s the community hall of my childhood, complete with what looks like my Dad’s truck. The approach I am recalling is from the opposite direction, along that fence on the right side of this photo.

To complicate matters, the hall was located at a fork in the road on the north side of the Fraser River right at the foot of a landmark bridge. Yes, I had some further detailing to drop into my scene, adding yet another ‘layer’ or plane, if I truly wanted the scene recognizable to others. So my perspective was more ‘western’ than oriental, I had an extra plane to incorporate, I had snow to depict in all its nuances, and I had deciduous western trees to portray, not the conventional oriental pines I do know how to cover with snow….

This is a more recent incarnation of the Fraser River Bridge crossing near Dunster BC. The photo (credit Bill Arnold) was taken facing southwest (away from the hall) and gives an idea of the shape of the Caribou Mountains in the background.

How did I get myself into this situation and could I paint myself out of it? Oh, and did I mention I started laying out this composition in an art group painting session, meaning I had the added pressure of potential friendly queries as to how my painting was coming along! Of course that last bit of “pressure” also comes with positive encouragement, helpful direction, and expert critiquing. Hurrah for art groups.

My painting progress

To say my painting went through several transformations would be understatement. When I wasn’t actively doctoring my scene, the image would loom up in my mind and I’d mentally adjust elements. I also left the painting lying on my art table where I could take frequent peeks and let ideas float around.

Step 1: With a preliminary sketch worked out (see above) I selected a clean sheet of Moon Palace and lightly transferred my main lines to the paper using a small brush and pale indigo ink. Such ‘first lines’ easily disappear into a scene as you enhance shapes and elements with ink and color. Furthermore, with my scene intended to be a winter scene, if any of these first lines were to later become ‘false lines’ I could pass them off as snowdrifts. My main lines were the distant mountain ridges, the river banks and bridge, the community hall and surrounding fence, the silhouettes of the horse rear-ends, the snowy tracks of the roadways, and the bushes at either side of the road.

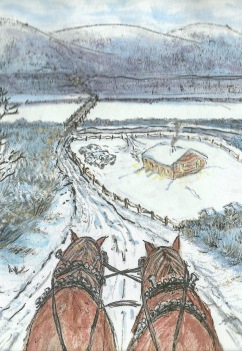

Step 2: Adding textures and details with ink and mostly a dry brush came next. I easily added the harnesses and defining manes to my horses. Our horses had been a white mare (Lou) and a grey stallion (Rocky) but in the interests of scenic impact I planned to paint two chestnut mares. The dark brown would offer better contrast to the snowy scene and help focus attention where I most wanted it.

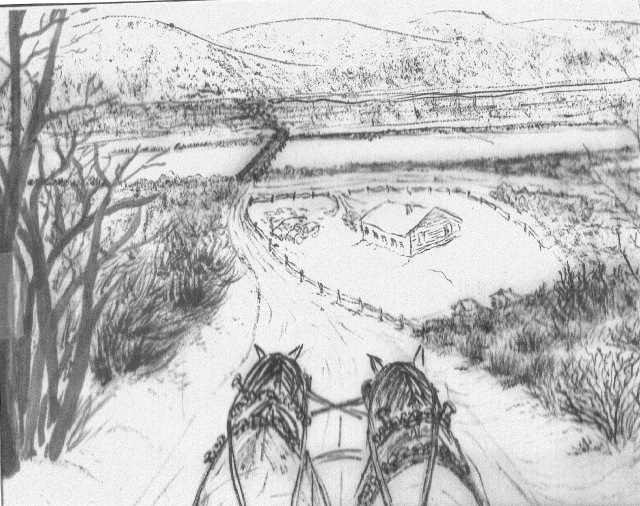

This is a photocopy I made of my preliminary ‘texturing’ of the landscape. the aim is to have greater detail showing in the foreground and less clarity or details further away. I tried to angle and curve the road for an interesting perspective on the scene.

My distant mountains were given a rough brushing to suggest tree cover. The bridge of the time had low railings and was slightly wider than the width of a single vehicle. Leaving a pure white expanse for the river was simple enough; defining the siding of the wooden structure that was the community hall at the time required a bit of research. I consulted old photos for the roofline, number of windows and positioning on the lot. I recalled two-tier barbed-wire fencing strung between fence posts and dropped those in. Then my landscape painting bogged down.

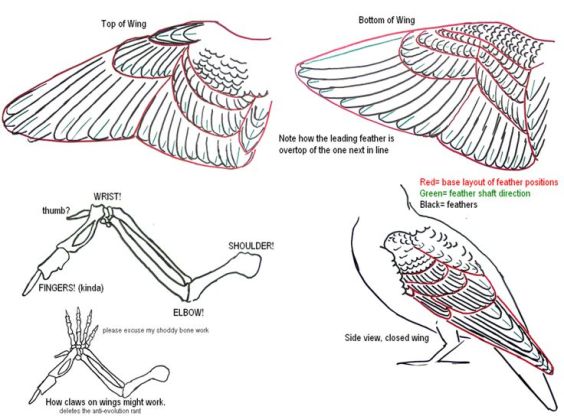

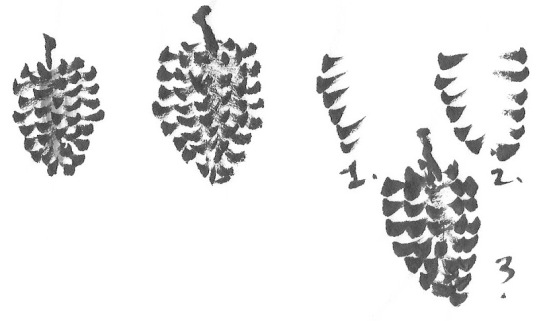

I faced two challenges—1. How to define trees and bushes on either side of my roadway with gradually diminishing definition as the eye moved from foreground to middle to far distance, and 2. How to cover everything with ‘snow’.

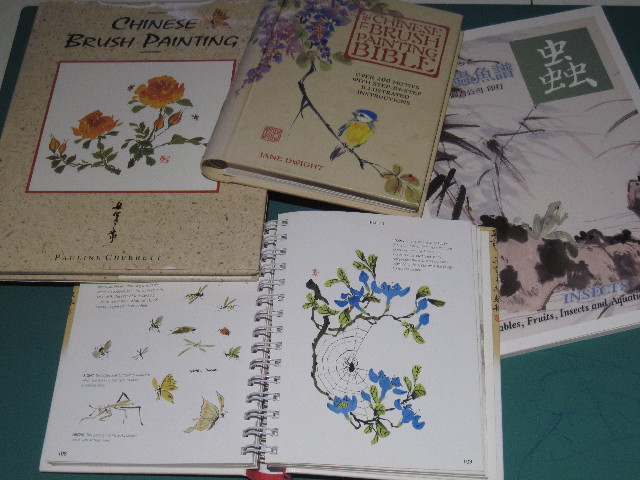

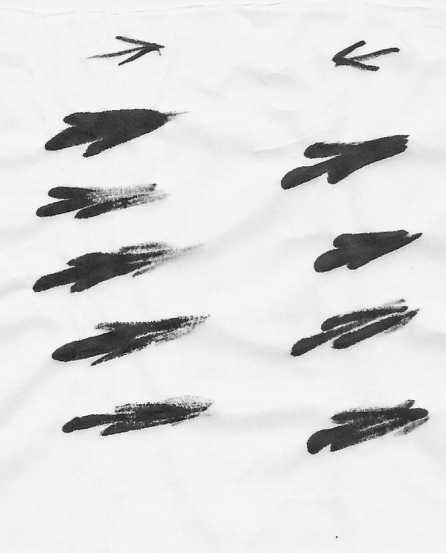

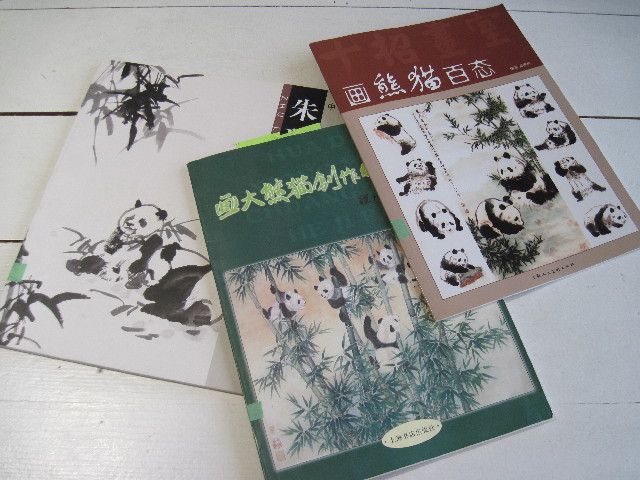

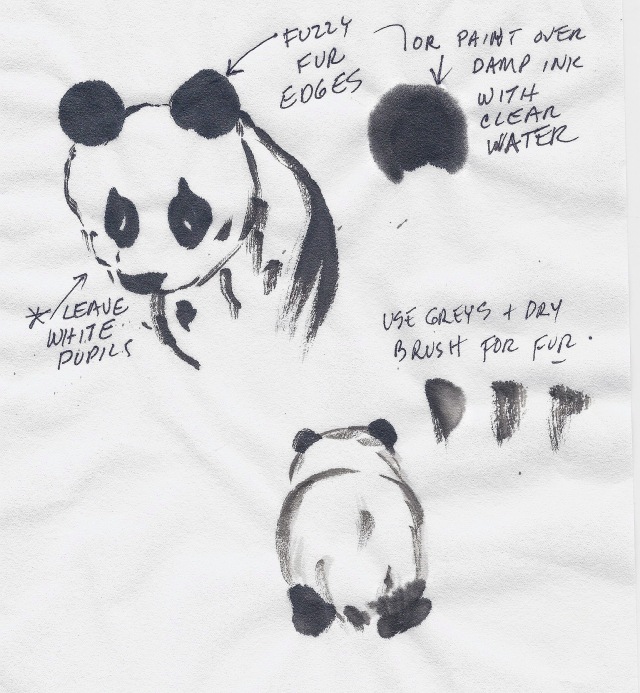

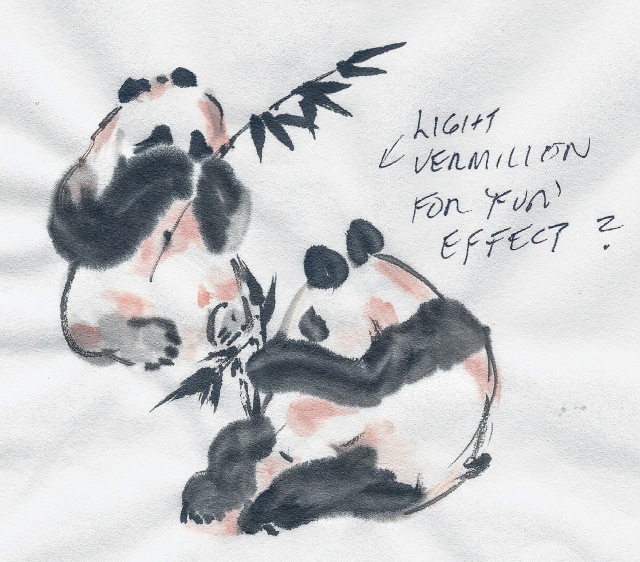

At this stage I stopped and researched ways of depicting dried grasses, low bushes, and deciduous trees such as poplar, willow and birches in winter. Most of my findings pertained to painting with oils or acrylics. I gathered some old Christmas card and calendar scenes filed away for just such ‘kick-start’ thinking and hunted on the Internet for watercolor treatments of snowy, winter roadside scenes.

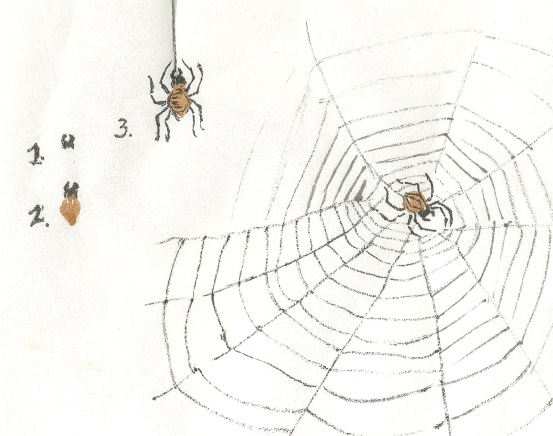

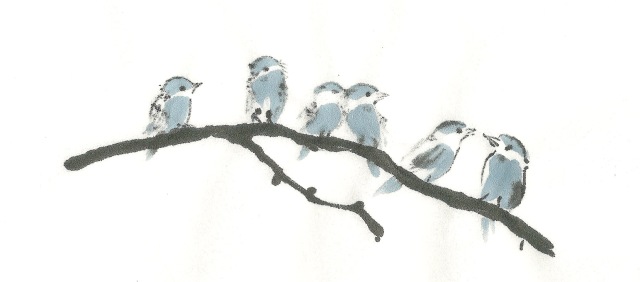

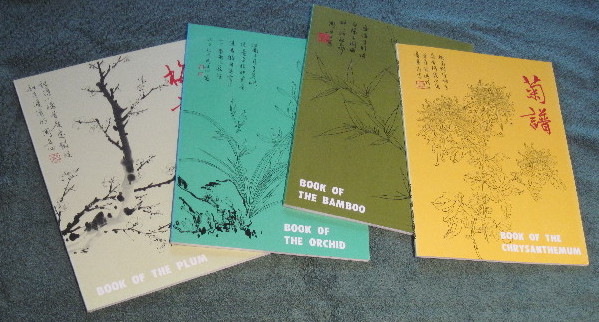

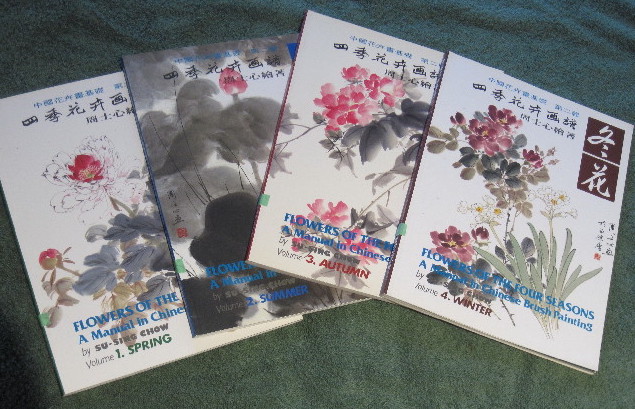

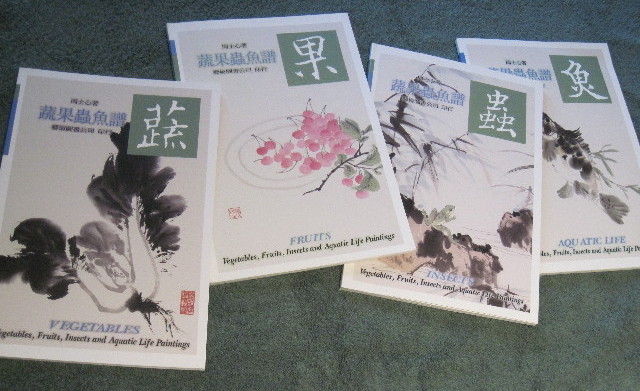

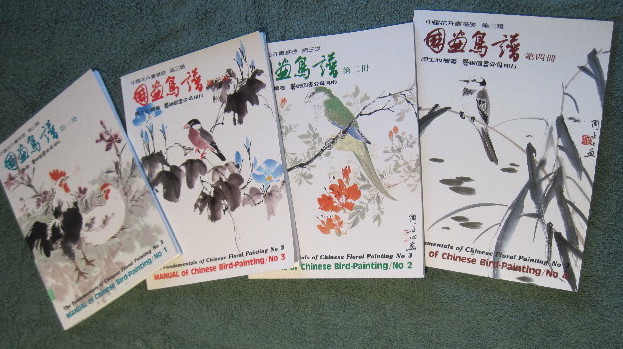

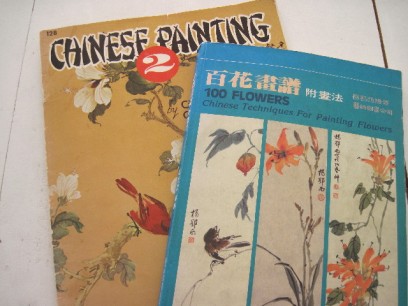

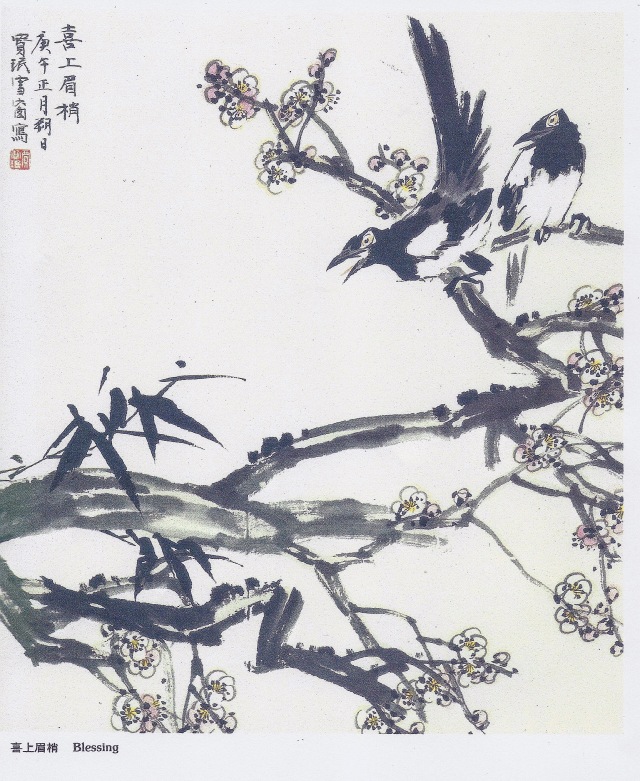

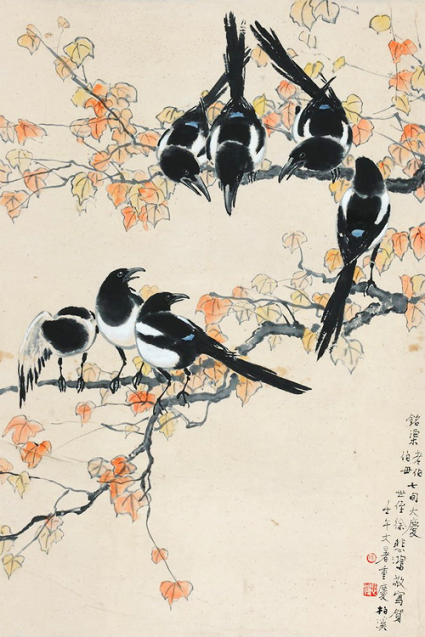

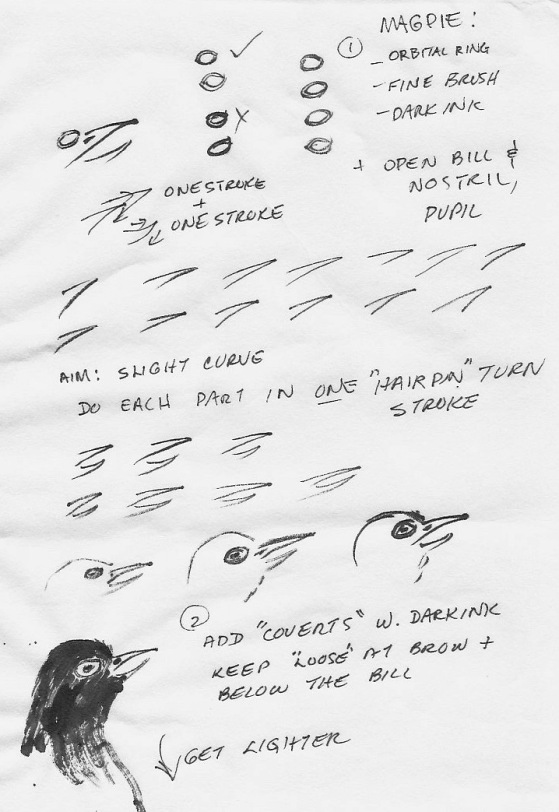

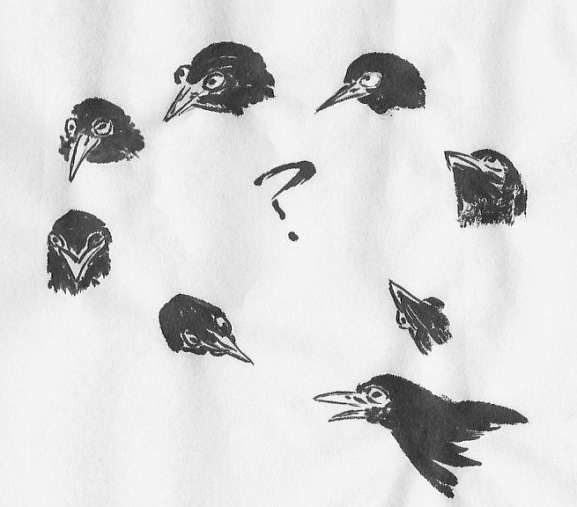

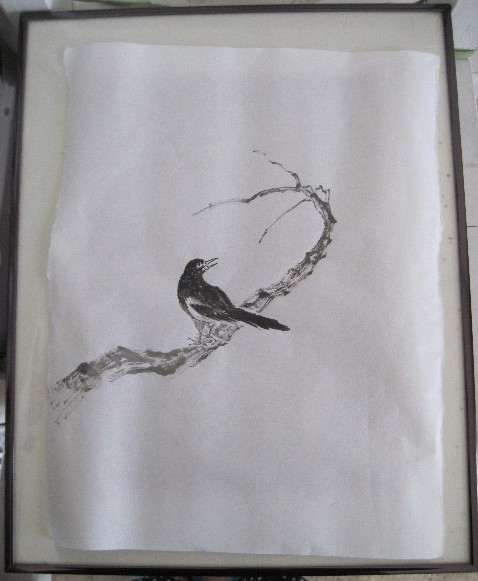

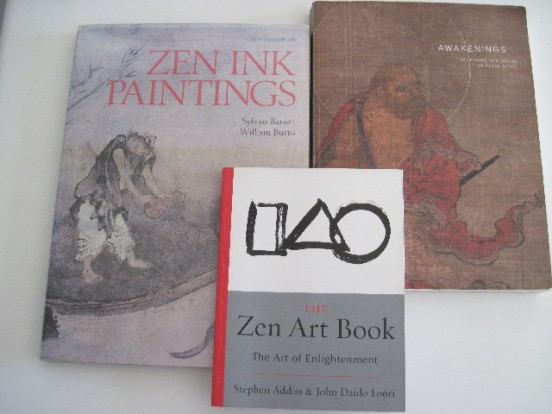

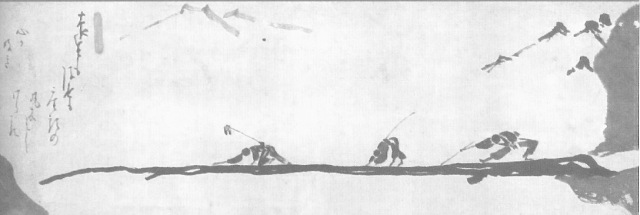

I had previously rifled through all possible Chinese brush painting (CBP) instructions on landscape painting, on my shelves and on the Internet, and amassed a slim file of ‘maybe’ techniques. Western scenes such as the one I aimed to depict have not been widely treated in this manner. Here are some thumbnail images of items I consulted for inspiration and guidance:

Knowing the most likely successful approach would be to define tree silhouettes, bushes and grasses with ink (or maybe color), create shading and depth with indigo, and then wash the scene in blues to suggest early evening light (gloam) I tested some possibilities on smaller bits of paper. I went ahead and tried some of those methods, then had to re-create my landscape from scratch. More than once!

It was tricky to figure out a satisfying overlapping of bushes at either side of the road to help enhance the depth within the picture and ‘frame’ the focal point of the vignette. I would have liked using evergreens (at one stage that is what I did on the right hand side) as I knew how to use them, BUT they were not ‘right’ for my true-life scene; they grew further back from the roadside. Horses of a different color would never matter to other observers, but inauthentic landscape elements would. I had to figure out the darn trees.

Step 3: Adding color. I painted in pale yellow light spewing from the hall windows, used burnt sienna in the grasses, washed chestnut shades over my horses, and added snowdrift and snow bank lines (thin ink lines first, followed by blue snow shadowing). I dabbed in white paint in the foreground to depict snow clumps on branches. With the line definition complete, the texturing in place, and main elements colorized it was time to wash the whole in blues to try and capture the late afternoon winter light.

With my whole painting dry, I wet my distant mountains and colored them with a light indigo wash. I added purple tones to the mountain bases. I wet the rows of bushes along the river and gave them purple/blue tones. I treated the bushes on either side of my road similarly, striving to keep sky and snowy fields white. With a small brush I then trailed in blue shadows along the roadways, ditches, and fence lines. The shiny bells on my horse harnesses required some white paint to enhance their look, make them pop.

Step 4: Final tweaking. As with any painting, landscape or otherwise, it helps to step back from time to time and examine it as a whole, looking for things that work and those that need touch-ups. As my intention was to use this scene for an art card, I dropped small black mats over it from time to time to “see” how it was shaping up.

I pack plain black matts in 8 x 11 and 5 x 7 inch sizes in my art bag to aid in planning paintings so that they meet pleasing and useful proportions.

Even now, after accepting the above image to be as ‘finished’ as possible days ago, I can see that some branches in the clump of bushes on the left should be dabbed with more snow caught in the vees and upper surfaces.

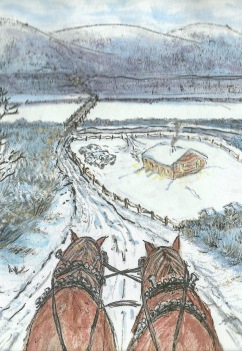

Concerned that the horses lost their dominance when the scene was fleshed out on either side of the road, I used a smaller mat to capture less of the scene.

My final landscape:

After gluing and drying the painting, I scanned it in and created a card. It seemed to need the added ‘oomph’ of blue borders.

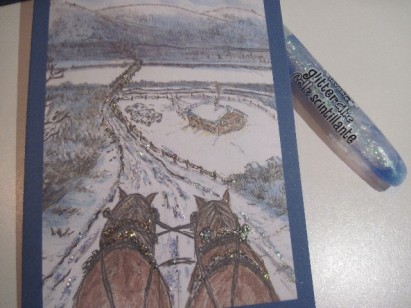

And then because I have some grandchildren who love glitter-glue….

Reflections:

I love the horses and other main scene elements. I want to work more with snow and bushes/trees at mid and far distances. It’s not easy making artistic decisions when you have a particular scene in mind, and want to ‘keep it real’. I had several old photos of the hall to help guide me but none showing the true shapes of the far mountain ridges (Caribou range of the Columbias.) We all seem to have taken photos pointing in the opposite direction, toward the Rocky Mountain range. And of course, once started on revisiting old memories many more come to mind as painting subjects.

The clash between what is/was real and what works for a painting can literally ruin your intentions. The inspirational scene, although having at least three ‘distances’ (front, mid range and far), comprised essentially three, layered, horizontal planes. And

The clash between what is/was real and what works for a painting can literally ruin your intentions. The inspirational scene, although having at least three ‘distances’ (front, mid range and far), comprised essentially three, layered, horizontal planes. And